A hundred virgins join a hundred swains,

And fond Adonis leads the sprightly trains;

Pair after pair, along his sacred groves

To Hymen’s fane the bright procession moves;

Each smiling youth a myrtle garland shades,475

And wreaths of roses veil the blushing maids;

Light Joys on twinkling feet attend the throng,

Weave the gay dance, or raise the frolic song;

—Thick, as they pass, exulting Cupids fling

Promiscuous arrows from the sounding string;480

On wings of gossamer soft Whispers fly,

And the sly Glance steals side-long from the eye.

—As round his shrine the gaudy circles bow,

And seal with muttering lips the faithless vow,

Licentious Hymen joins their mingled hands,485

And loosely twines the meretricious bands.—

Thus where pleased Venus, in the southern main,

Sheds all her smiles on Otaheite’s plain,

Wide o’er the isle her silken net she draws,

And the Loves laugh at all but Nature’s laws.”490

Here ceased the Goddess,—o’er the silent strings

Applauding Zephyrs swept their fluttering wings;

Enraptur’d Sylphs arose in murmuring crowds

To air-wove canopies and pillowy clouds;

Each Gnome reluctant sought his earthy cell,495

And each bright Floret clos’d her velvet bell.

Then, on soft tiptoe, Night approaching near

Hung o’er the tuneless lyre his sable ear;

Gem’d with bright stars the still etherial plain,

And bad his Nightingales repeat the strain.500

Adonis. l. 468. Many males and many females live together in the same flower. It may seem a solecism of language, to call a flower, which contains many of both sexes, an individual; and more so to call a tree or shrub an individual, which consists of so many flowers. Every tree, indeed, ought to be considered as a family or swarm of its respective buds; but the buds themselves seem to be individual plants; because each has leaves or lungs appropriated to it; and the bark of the tree is only a congeries of the roots of all these individual buds. Thus hollow oak-trees and willows are often seen with the whole wood decayed and gone; and yet the few remaining branches flourish with vigor; but in respect to the male and female parts of a flower, they do not destroy its individuality any more than the number of paps of a sow, or the number of her cotyledons, each of which includes one of her young.

The society, called the Areoi, in the island of Otaheite, consists of about 100 males and 100 females, who form one promiscuous marriage.

—from J. E. Smith’s English Botany

With bliss botanic1 as their bosoms heave,

Still

pluck forbidden fruit, with mother Eve,

For puberty in sighing

florets pant,

Or point the prostitution of a plant;

Dissect2 its organ of unhallow’d lust,

And

fondly gaze the titillating3 dust;4

With

liberty’s sublimer views expand,5

And

o’er the wreck of kingdoms6 sternly stand;

And,

frantic, midst the democratic storm,

Pursue, Philosophy! thy

fantom-form.7

1 Botany has lately become a

fashionable amusement with the ladies. But how the study of the

sexual system of plants can accord with female modesty, I am not

able to comprehend. See not from Darwin’s Botanic Garden, at

p.

I had, at first, written;

More eager for illicit knowledge,

pant,

With lustful boys

anatomize a plant;

The

virtues of its dust prolific speak,

Or point its pistil with unblushing

cheek.

I have, several times, seen boys and girls

botanizing together.

2 Miss Wollstonecraft does not blush to say, in an introduction to a book designed for the use of young ladies, that, “in order to lay the axe at the root of corruption, it would be proper to familiarize the sexes to an unreserved discussion of those topics, which are generally avoided in conversation from a principle of false delicacy; and that it would be right to speak of the organs of generation as freely as we mention our eyes or our hands.” To such language our botanizing girls are doubtless familiarized: and, they are in a fair way of becoming worthy disciples of Miss W. If they do not take heed to their ways, they will soon exchange the blush of modesty for the bronze of impudence.

3 “Each pungent grain of titillating dust.” Pope.

4 “The prolific dust”—of the botanist.

5 Non vultus,

non color unus,

Non comptae mansere comae: sed pectus

anhelum,

Et rabie fera corda tament; majorque videri, &c.

Except the non color unus, Virgil’s Sibyll seems to be an

exact portrait of a female fashionist, both in dress and

philosophism.

6 The female advocates of Democracy in this country, though they have had no opportunity of imitating the French ladies, in their atrocious acts of cruelty; have yet assumed a stern serenity in the contemplation of those savage excesses. “To express their abhorrence of royalty, they (the French ladies) threw away the character of their sex, and bit the amputated limbs of their murdered countrymen.—I say this on the authority of a young gentleman who saw it.—I am sorry to add, that the relation, accompanied with looks of horror and disgust, only provoked a contemptuous smile from an illuminated British fair-one.” See Robinson—p. 251.

7 Philosophism, the false image of philosophy.... A true description of philosophy which heretofore appeared not in open day, though it now attempts the loftiest flights in the face of the sun. I trust, however, to English eyes, it is almost lost in the “black cloud” to which it owed its birth.

From an apprehension that Botany in an English dress would become a favorite amusement with the Ladies; many of whom are very considerable proficients in the study, in spite of every difficulty; it was thought proper to drop the sexual distinctions in the titles to the Classes and Orders, and to adhere only to those of Number, Situation, &c.

Dr. Withering has given a Flora Anglica under the title of Botanical Arrangements, and in this has translated parts of the Genera and Species Plantarum of Linnæus; but has entirely omitted the sexual distinctions, which are essential to the philosophy of the system; and has introduced a number of english generic names, which either bear no analogy to those of Linnæus, or are derived from such as he has rejected, or has applied to other genera; and has thus rendered many parts of his work unintelligible to the latin Botanist; equally difficult to the english scholar; and loaded the science with an addition of new words.

We propose to give a literal and accurate translation of the SYSTEMA VEGETABILIUM of LINNAEUS, which unfolds and describes the whole of his ingenious and elaborate system of vegetation.

—by Mary Delany

The British Museum

Dear Sister, Shrubbery, February 1.

As it is an unusual thing for us to be separated, I do not doubt but we equally feel the pain of being at a distance from each other.... My fondness for flowers has induced my mother to propose Botany, as she thinks it will be beneficial to my health, as well as agreeable, by exciting me to use more air and exercise than I should do, without such a motive; because books should not be depended upon alone, recourse must be had to the natural specimens growing in fields and gardens. How should I enjoy this pursuit in your company, my dear sister! but as that is impossible at present, I will adopt the nearest substitute I can obtain, by communicating to you the result of every lesson.... Farewell.

FELICIA.

An outline of Botany may be learnt from Lee’s introduction to botany, and from translation of the works of Linnæus by a society at Lichfield; to which might be added Curtis’s botanical magazine, which is a beautiful work, and of no great expense. But there is a new treatise introductory to botany called Botanic dialogues for the use of schools, well adapted to this purpose, written by M. E. Jacson, a lady well skilled in botany, and published by Johnson, London. And lastly I shall not forbear to mention, that the philosophical part of botany may be agreeably learnt from the notes to the second volume of the Botanic garden, whether the poetry be read or not.

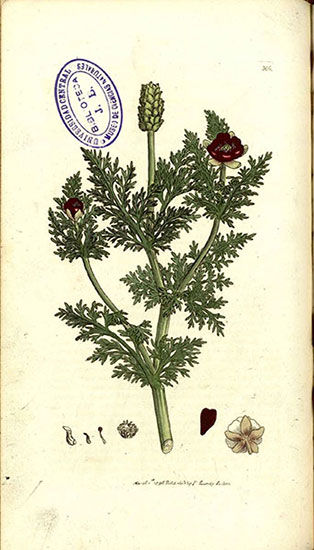

| Class: | 13. Polyandria (Many Males) |

| Order: | 12. Polygynia (Many Females) |

| Genus: | Adonis |

| Species: | Adonis annua |

| Class: | Equisetopsida C. Agardh |

| Sub- class: |

Magnoliidae Novák ex Takht. |

| Super- order: |

Ranunculanae Takht. ex Reveal |

| Order: | Ranunculales Juss. ex Bercht. & J. Presl |

| Family: | Ranunculaceae Juss. |

| Genus: | Adonis L. |

| Species: | Adonis annua L. |

Hark to my call, ye souls of noble fires!

Whom birth emboldens, and whom taste inspires.

Bee-like, my muse pursues her devious way,

To glean instructions for the fair and gay.

Omiah’s isle her best regards employs,

Its leagues of love, and commonwealth of joys (h).

Illustrious train! whose vast invention shames

The noblest licence of our modish dames;350

Hail, happy few! whom clearer views refine,

Exalted spirits, touch’d with ray divine.

The courtly fair, and high-born striplings rove,

In blest alliance of promiscuous love;

They shun the curse domestic druges bear,

And taste the social bliss without a fear.

The couch of joy from vile restraint is free’d,

The little tell-tales of its pleasures bleed.

No maid is toasted in Omiah's land,

Nor youth in fashion, till he joins their band.360

They the ton, o’er etiquette preside,

Direct amusements, and opinions guide,

Hear their bon-mots retail’d from town to town,

And teach the public when to smile or frown.

’Tis theirs alone with dignity to range,

Where female honor is eternal change;

The various paths of pleasure, and of fame,

Disjoin’d for others, are for them the same.

(h) Vide in Hawkesworth’s Voyages an account of a most extraordinary association.

TO DR. DARWIN, ON READING HIS LOVES OF THE PLANTS.

No Bard e’er gave his tuneful powers,

Thus to traduce the fame of flowers;

Till Darwin sung his gossip tales,

Of females woo’d by twenty males.

Of Plants so given to amorous pleasure;

Incontinent beyond all measure.

He sings that in botanic schools,

Husbands* adopt licentious rules;

Plurality of Wives they wed,

And all they like—they take to bed.

That Lovers sign with secret love,

And marriage rites clandestine, prove.

That, fann’d in groves their mutual fire,

They to some Gretna Green retire.

*See classes of Flowers, Polygamy, Clandestine Marriage, &c.

—from by Jane Loudon’s The Ladies Flower-Garden

A very considerable number of the principal people of Otaheite, of both sexes, have formed themselves into a society, in which every woman is common to every man; thus securing a perpetual variety as often as their inclination prompts them to seek it, which is so frequent, that the same man and woman seldom cohabit together more than two or three days.

These societies are distinguished by the name of Arreoy; and the members have meetings, at which no other is present, where the men amuse themselves by wrestling, and the women, notwithstanding their occasional connection with different men, dance the Timorodee in all its latitude, as an incitement to desires which it is said are frequently gratified upon the spot. This, however, is comparatively nothing. If any of the women happen to be with child, which in this manner of life happens less frequently than if they were to cohabit only with one man, the poor infant is smothered the moment it is born, that it may be no encumbrance to the father, nor interrupt the mother in the pleasures of her diabolical prostitution.

Next Species: