Meadia’s soft chains five suppliant beaux confess,

And hand in hand the laughing belle address;

Alike to all, she bows with wanton air,

Rolls her dark eye, and waves her golden hair.

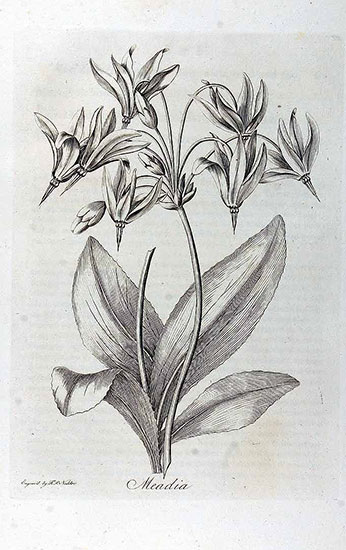

Meadia. l. 61. Dodecatheon, American Cowslip. Five males and one female. The males, or anthers, touch each other. The uncommon beauty of this flower occasioned Linnæus to give it a name signifying the twelve heathen gods; and Dr. Mead to affix his own name to it. The pistil is much longer than the stamens, hence the flower-stalks have their elegant bend, that the stigma may hang downwards to receive the fecundating dust of the anthers. And the petals are so beautifully turned back to prevent the rain or dew drops from sliding down and washing off this dust prematurely; and at the same time exposing it to the light and air. As soon as the seeds are formed, it erects all the flower-stalks to prevent them from falling out; and thus loses the beauty of its figure. Is this a mechanical effect, or does it indicate a vegetable storgé to preserve its offspring? See note on Ilex, and Gloriosa.

The beautiful Umbel of Dodecatheon (Meadia) derives its peculiar elegance from the pendent direction of its flexile peduncles; by which position the pistil, being much longer than the stamens, receives with more certainty the dust of the anthers. The fertilization of the seeds is being thus secured, their protection is to be next provided for; and this we see effected by a sudden change of position in the footstalks, from a pendent to an erect position; the former rendering the seeds liable to be lost before they have attained to a state of maturity, and the latter preserving them securely in their seed-vessels, until ripe for dispersion.

—by Jan Koeman, Tuolumne Camping Ground,

Yosemite Natural Park, California, USA

STANZAS

Written Near a Certain Clergyman’s Garden

A GARDEN he has, and that we are agreed on,

But not of the sort that lie eastward in Eden:*—

The nose or the eye here is little treat,

And, what is still worse, there is little to eat....

Some poppies, indeed, he is careful to keep,

Which, much like some sermons, incline us to sleep:

But, for primrose, or snow-drop, or cowslip—as soon

You might find in this garden a Spanish doubloon....

This garden of gardens where nothing is sown

But contemptible plants, and of eatables none,

Where all is so meager, and all is so lean,

And never the step of a female was seen,

Assures us no Satan will ever come here,

To search for a woman, or look for good cheer;

Not an angel a-near it the townsmen will find,

Nor a snake from the swamp—to be-devil mankind.

* Genesis, chap. ii. verse 8.

—illustrated by William Blake and engraved by F. P. Nodder,

The Botanic Garden

| Class: | 5. Pentandria (Five Males) |

| Order: | I. Monogynia (One Female) |

| Genus: | Dodecatheon |

| Species: | Dodecatheon meadia |

| Class: | Equisetopsida C. Agardh |

| Subclass: | Magnoliidae Novák ex Takht. |

| Super- order: |

Asteranae Takht. |

| Order: | Ericales Bercht. & J. Presl |

| Family: | Primulaceae Batsch ex Borkh. (Primrose Family) |

| Genus: | Dodecatheon L. |

| Species: | Dodecatheon meadia L. |

CLASS V.

PRIMULA

Primrose.u

PENTANDRIA, MONOGYNIA

As fell Disease with scowling eye advanc’d,v

At my soul’s lord her deadly shaft she lanced;

Round his fine brow her poison’d wreath she wove,

And to dark cypress chang'd the flow'rs of love:

Sad, o'er his mournful couch, Despair was seen

To hang with frantic grief and haggard mien;

While fond Affection clasped him to her heart,

And shriek’d in agony, “Tis death to part;

Live, live for me!” in piercing tones she cried,

On her wan lips the fault’ring accents died;

“Thy Anna’s voice was wont to raise a smile,

Soothe thy dark brow, thy pensive cares beguile:

Can it not give thee to my longing arms,

Restore thee health, and ease my sad alarms?...

“How oft, lov’d Primula, my tortur’d breast

Sought in thy bow’rs a momentary rest;

Oft on thy charms with heavy eye I gaz’d,

And sigh’d o’er beauties that my hand had rais’d.

Five tender brothers form’d thy modest train,

And sooth’d my woes with music’s heav’nly strain;

Thy gentle hand wip’d my fast falling tears,

Cheer’d me with hope, and calm’d my anxious fears:

The hope you have with joy my bosom fir’d,

And with salvation’s pow’r my arm inspir’d.

u Five stamens, one pistil. It belongs to a natural order called Preciae, from precius, early ripe, and comprehends such plants as flower early in the spring: their general characters are a monophyllous quinquefid permanent calyx, a monopetalous quinquefid corolla, and a capsule for a seed-vessel, superior or inclosed within the calyx....

v These lines were written at the request of a friend, who, during a dangerous indisposition of her husband, found her only relaxation from the confinement of a sick room in visiting her greenhouse, and among its flowers she watched with peculiar pleasure the expansion and growth of this favorite Primrose.

Next Species: