BOTANIC MUSE! who, in this latter age

Led by your airy hand the Swedish sage,

Bade his keen eye your secret haunts explore

On dewy dell, high wood, and winding shore;

Say on each leaf how tiny graces dwell; 35

How laugh the Pleasures in a blossom’s bell;

How insect Loves arise on cobweb wings,

Aim their light shafts, and point their little stings.

“First the tall Canna lifts his curled brow

Erect to heaven, and plights his nuptial vow; 40

The virtuous pair, in milder regions born,

Dread the rude blast of Autumn’s icy morn;

Round the chill fair he folds his crimson vest,

And clasps the timorous beauty to his breast.

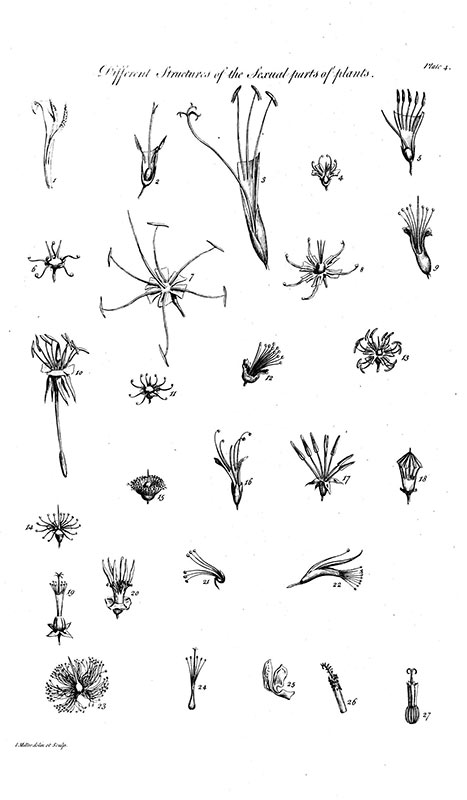

Canna. l. 39. Cane, or Indian Reed. One male and one female inhabit each flower. It is brought from between the tropics to our hot-houses, and bears a beautiful crimson flower; the seeds are used as shot by the Indians, and are strung for prayer-beads in some catholic countries.

—from Erasmus Darwin et al., A System of Vegetables

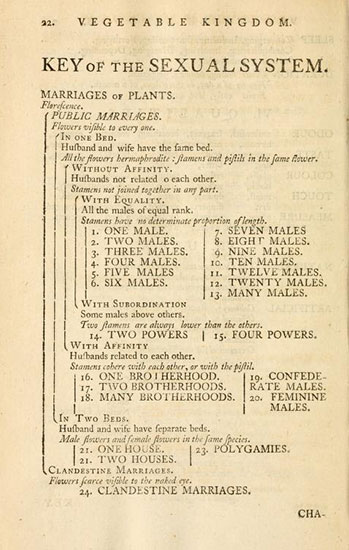

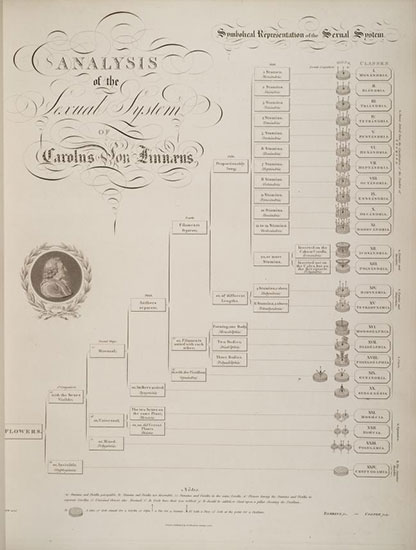

CLASS I.

CANNA

Indian flowering Reed.b

MONANDRIA, MONOGYNIA

From the tall Canna’s sable polish’d seeds

The pious nun prepares her holy beads;

While at her shrine she seeks almighty grace,

The savage Indian shoots the feather’d race:

Arm’d with those beads that mark her sacred pray’r,

He hurls destruction through the trackless air.

A gallant youth, in crimson vest array’d,

Supplies the Indian, and the cloister’d maid.

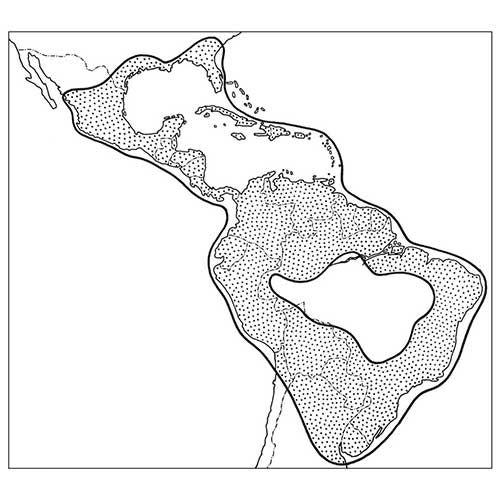

b A native of both Indies; the flower are produced in large spikes, and are of a bright scarlet: they are succeeded by a fruit or capsule, oblong, rough, and crowned with the three-cornered empalement of the flower which remains. When the fruit is ripe, the capsule opens lengthwise into three cells, filled with round, shining, black and hard seeds, which are used by the Indian as shot, and strung for prayer beads in some catholic countries.

H. Maas-van de Kamer & P. J. M. Maas,

The Cannaceae of the World

(Blumea, vol. 53, no. 2, 2008, pp. 247—318: 274)

—from Robert John Thornton’s Temple of Flora

—from Robert John Thornton’s Temple of Flora

| Class: | I. Monandria (One Male) |

| Order: | I. Monogynia (One Female) |

| Genus: | Canna |

| Species: | Canna Indica |

| Class: | Equisetopsida C. Agardh |

| Subclass: | Magnoliidae Novák ex Takht. |

| Super- order: |

Lilianae Takht. |

| Order: | Zingiberales Griseb. |

| Family: | Cannaceae Juss. (Canna Family) |

| Genus: | Canna L. |

| Species: | Canna indica L. |

Where sacred Ganges* proudly rolls

O’er Indian plains his winding way,

By rubied rocks and arching shades†,

Impervious to the glare of day,

Bright Canna veil’d in Tyrian robe,

Views her lov’d lord with duteous eye;

Together both united bloom,

And both together fade and die.—

Thus, where Benares’‡ lofty towers

Frown on her Ganges’ subject wave,

Some faithful widow’d bride repairs,

Resolv’d the raging fire to brave.

True to her plighted virgin vow

She seeks the altar’s radiant blaze

Her ardent prayers to Brahma§ pours,

And calm approaching death surveys.

With India’s gorgeous gems adorn’d,

And all her flowers, which loveliest blow:

“Begin,” she cries, “the solemn rites,

“And bid the fires around me glow.

“A cheerful victim at that shrine

“Where nuptial truth can conquer pain,

“Around my brow rich garlands twine,

“With roses strew the hallow’d plain....”

* Where sacred Ganges.] The Ganges has been celebrated in all ages not only on account of the clearness of its water, which does not become putrid, though kept for years, as also for its sanctity. This water is conveyed to great distances, being esteemed necessary in the performance of certain religious ceremonies. All parts of the Ganges are said to be holy, but some particular parts are accounted to be more so than others, to which places thousands resort at certain seasons of the year, in order to purify themselves.

† Arching shades.] Poetry and painting are called kindred arts; but the former oftentimes rises superior to the powers of the latter.... Thus we could not introduce in our background the Ficus Religiosa, or Indian Fig-tree, (called so from its producing a delicious fruit, of a bright scarlet color, shaped like a fig,) overshadowing one of the noblest rivers in India. This tree rises much higher than our tallest oaks, and then sends out from the top lateral branches, and from thence drop other branches, which, reaching the ground, take root, and become trees, so that the canopy above continually extends, and furnishes new supports; thus constituting a forest of a single tree, under the shade of which 10,000 persons have been known, upon religious occasions, to repose.

‡ Benares’ lofty towers.] Benares is one of the most ancient cities of Indostan; and besides temples dedicated to almost innumerable deities (the fancies of the mind), it once boasted a pagoda (or sacred temple) of an immense size, in the center of the city. This was situate [sic] close to the shore of the Ganges, into which stream, according to the account of Tavernier, a regular flight of steps descend, leading directly down from the gates of the pagoda. The body of this temple is constructed in the form of a vast cross, allusive to the four elements, with a very high cupola in the center of the building, but somewhat pyramidal towards the summit; and at the extremity of every one of the four parts of the cross there is a tower, to which there is an ascent on the outside, with balconies at stated distances, affording delightful views of the city, the river, and adjacent country....

§ To Brahma pours.] The subject is so extremely interesting, that of the great God himself, the author of our being, omniscient, omnipresent, and omnipotent, that the reader will forgive our entering widely here into the discussion of primitive religion, in order to prove that in all Nations the wise have worshiped one only supreme God, but the vulgar the pictures of his attributes....

Next Species: