Weak with nice sense, this chaste Mimosa stands

From each rude touch withdraws her timid hands;

Oft as light clouds o’er-pass the Summer-glade,

And feels, alive through all her tender form, 305

The whisper’d murmurs of the gathering storm;

Shuts her sweet eye-lids to approaching night,

And hails with freshen’d charms the rising light.

Veil’d, with gay decency and modest pride,

Slow to the mosque she moves, an eastern bride; 310

There her soft vows unceasing love record,

Queen of the bright seraglio of her Lord.—

So sinks or rises with the changeful hour

The liquid silver in its glassy tower.

So turns the needle to the pole it loves, 315

With fine libations quivering, as it moves.

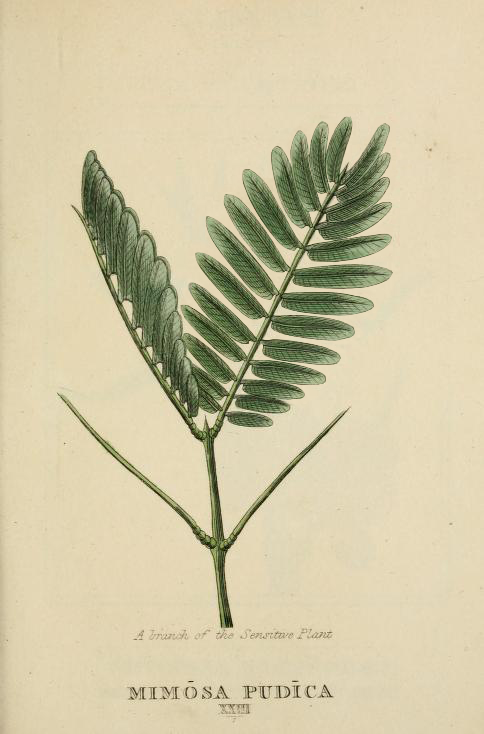

Mimosa. l. 321. The sensitive plant. Of the class Polygamy, one house. Naturalists have not explained the immediate cause of the collapsing of the sensitive plant; the leaves meet and close in the night during the sleep of the plant, or when exposed to much cold in the day-time, in the same manner as when they are affected by external violence, folding their upper surfaces together, and in part over each other like scales or tiles; so as to expose as little of the upper surface as may be to the air; but do not indeed collapse quite so far, since I have found, when touched in the night during their sleep, they fall still further; especially when touched on the foot-stalks between the stems and the leaflets, which seems to be their most sensitive or irritable part.

CLASS XXIII.

MIMOSA

Sensitive Plant.y

POLYGAMIA, MONOECIA

As some young maid, to modest feeling true,

Shrinks from the world, and veils her charms from view,

At each slight touch her timid form receives,

The fair Mimosa folds her silken leaves;

And feel th’ alternate change of night and day;

For when her mantle dusky Ev’ning throws,

She droops her head, and sinks to soft repose;

Nor till the morn dispels the shades of night,

Rears her meek brow, and wakes to life and light.

y Mimosa.—Various situations, stamens only, pistils only, or both stamens and pistils. Linnæus reckons there are near ninety species of this curious genus, all of them natives of warm climates. They are named Mimosa, which signifies mimic, from the singular sensibility of the leaves of some of the species, which, by their motion, mimic or imitate as it were the motion of animals. For by the slightest touch the leaves contract and close themselves; and during wind and rain, at night, and when expose to much cold in the day, the leaves meet and close in the same manner as when touched.

The vibration of the parts is that which keeps the leaves of the sensitive plant in their expanded and elevated state: This is owing to a delicate motion continued through [e]very fiber of them. When we touch the leaf, we give it another motion more violent than the first: this overcomes the first: the vibration is stopped by the rude shock: and the leaves close, and their footstalks fall, because that vibrating motion is destroyed, which kept them elevated and expanded.

For the Sensitive Plant has no bright flower;

Radiance and odor are not its dower;

It loves, even like Love, its deep heart is full,

It desires what is has not, the beautiful!...

When winter had gone and spring come back,

The Sensitive Plant was a leafless wreck;

But the mandrakes, and toadstools, and docks, and darnels,

Rose like the dead from their ruined charnels....

That garden sweet, that lady fair,

And all sweet shapes and odors there,

In truth have never pass’d away:

’Tis we, ’tis ours, are changed; not they.

For love, and beauty, and delight,

There is no death nor change: their might

Exceeds our organs, which endure

No light, being themselves obscure.

—selections from Prometheus Unbound: A Lyrical Drama in Four Acts with Other Poems

| Class: | XIII. Polyandria (Many Males) |

| Order: | I. Monogynia (One Female) |

| Genus: | Mimosa |

| Species: | Mimosa pudica |

| Class: | Equisetopsida C. Agardh |

| Sub- class: |

Magnoliidae Novák ex Takht. |

| Super- order: |

Rosanae Takht. |

| Order: | Fabales Bromhead |

| Family: | Fabaceae Lindl. |

| Genus: | Mimosa L. |

| Species: | Mimosa pudica L. |

O Thou! who hast, so often

proved

The virtues of the plant,(a) beloved,—

That from the touch

recedes.—(b)

Assist, its magic to display;

For thou hast felt it every way,

And know’st how it

suc-ceeds.

(a) “A funnel-fashioned semi-quinquisid flower; its fruit is a long pod, containing a great many roundish seeds.” Owen.

(b) “The Sensitive Plant is so denominated from its remarkable property of receding from the touch, and giving signs as it were of animal life and sensation.” Owen.

—by Hrushikesh

IN the speculations, concerning the perceptive power of vegetables, which were read before this Society last spring, I observed, that the motions of the sensitive plant are not to be explained by the laws of electricity. For its leaves are alike affected by the contact of electric and nonelectric bodies; show the same sensibility whether the atmosphere be dry or moist; and instantly close when certain chemical stimuli, such as the vapor of vol. alkali, or the fumes of burning sulphur, are applied to them.

SWEET PLANT! with feelings exquisitively fine!

Emblem of female purity divine.

Nor boasts th’ enamel’d mead, or gay parterre,

So delicate a pattern for the fair.

In vain with trembling caution we approach,

The moest flow’r shrinks from the slightest touch.

In vain the hand that sunk, would raise again!

Virtue insulted spurns th’ offending swain,

Expiring like Lucretia with disdain

Pure, like this flow’r, and tremblingly alive,

Let each gay nymph instruction hence derive.

Avoid the open rake, th’ insidious foe,

Nor touch profane of impious hands allow,

To chastity devote, and pure as virgin-snow.

Next Species: