Our Herbarium: Dynamic Resource for Rapidly Changing World

Posted in Science on December 1 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Barbara Thiers, Ph.D., is Director of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium and oversees the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium. |

Part 1 in a 3-part series

The 7.3 million collections of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, the largest in the Western Hemisphere and among the four largest in the world, form the core of a beehive of activity. On a typical work day during the past year, our Herbarium staff of 29 full-time equivalents answered 28 requests for information via e-mail or phone, helped 10 visiting researchers use the Herbarium, sent 214 specimens on loan (over the year we sent to 38 countries and 38 states of the United States), added 360 new specimens, and digitized 400 specimens for sharing on-line through the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium.

The 7.3 million collections of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, the largest in the Western Hemisphere and among the four largest in the world, form the core of a beehive of activity. On a typical work day during the past year, our Herbarium staff of 29 full-time equivalents answered 28 requests for information via e-mail or phone, helped 10 visiting researchers use the Herbarium, sent 214 specimens on loan (over the year we sent to 38 countries and 38 states of the United States), added 360 new specimens, and digitized 400 specimens for sharing on-line through the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium.

Each herbarium specimen is a primary source of historical information about the Earth’s vegetation as well as about the person who collected it. The label that accompanies each specimen gives not only the name of the plant, but where and when it was collected, and by whom. Some labels give far more information, such as the name of the expedition, the funding source, and names of other members of the collecting party. Historical specimens often bear original handwriting, and sometimes notes, correspondence or sketches.

Although I’m inclined to think that everyone whose plant collections grace the Steere Herbarium is at least somewhat interesting, some of the plant collectors represented here are true celebrities—Charles Darwin, John C. Fremont, George Washington Carver, and John Cage, for example. Although the lives of these figures are very well documented, the specimens they collected still add a dimension to our understanding of their character.

As a child, I spent many weekends and school vacations accompanying my parents on collecting trips throughout California. My father, a professor at San Francisco State University, was documenting the mushrooms of the state, and was training graduate students to do likewise. Although at times I was an unwilling participant in these trips (especially as a teenager!) I always enjoyed my father’s excitement at an interesting find—an unknown species, or a familiar species growing in an unexpected place.

Years later I got to feel the thrill of my own field discoveries and also became acquainted with the real work of collecting—preserving and transporting specimens, labeling, identifying, and preparing them for accession into the Herbarium. This part of the work is exacting, sometimes tedious, often fraught with worry—with the rapid destruction of vegetation in some areas of the world, there may not be a second chance to re-collect a specimen that is lost, broken, or poorly dried.

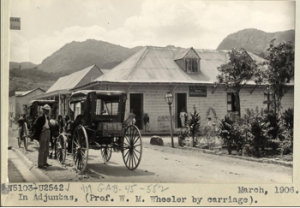

Advances in technology have allowed information gathering on field expeditions today to be far more comprehensive and precise than in the past. On early collecting expeditions, (photo at left is of a Botanical Garden expedition to Puerto Rico in 1906) scientists were often accompanied by artists who would sketch and paint the specimens as they were collected. Collection information was written in notebooks, and, due to a paucity of maps, collecting locations were described in terms of the length of time it took to walk or ride a horse from the nearest town. Today, we plan expeditions using databases and satellite images; we travel more often by jeep or helicopter, equipped with digital cameras and laptop computers to record information from collections as they are gathered. We determine the exact location of a collection site with a handheld global positioning device, and we prepare samples of each collection for DNA analysis back in the laboratory.

Advances in technology have allowed information gathering on field expeditions today to be far more comprehensive and precise than in the past. On early collecting expeditions, (photo at left is of a Botanical Garden expedition to Puerto Rico in 1906) scientists were often accompanied by artists who would sketch and paint the specimens as they were collected. Collection information was written in notebooks, and, due to a paucity of maps, collecting locations were described in terms of the length of time it took to walk or ride a horse from the nearest town. Today, we plan expeditions using databases and satellite images; we travel more often by jeep or helicopter, equipped with digital cameras and laptop computers to record information from collections as they are gathered. We determine the exact location of a collection site with a handheld global positioning device, and we prepare samples of each collection for DNA analysis back in the laboratory.

During the past year, 52,000 specimens were added to the Steere Herbarium. About 20,000 of these were collected by Garden scientists and students; the others were obtained as gifts or through exchange programs with other herbaria. Some of the specimens added this year represent species new to science, some represent species new to our Herbarium. Sometimes adding the 200th specimen of a species, or even the 1,000th, is just as significant as the first, because the more specimens we have of a species throughout time and space, the more we can learn about its relationships and response to environmental change.

What a concise and wonderful picture of not only how you categorize and preserve the history for collected plants but I enjoyed the wonderful glimse of your history as a child as well.

Thank you, Barbara!

Kathy