Empowering Girls Through Flowers

Posted in Science on June 23 2011, by Elizabeth McCarthy

| Elizabeth McCarthy is a post-doctoral researcher in the Genomics Program at NYBG. |

Recently, I had the opportunity to help introduce a group of bright junior high school girls to the science behind the beauty of flowers.

Back in March, I volunteered at the Explore Your Opportunities–The Sky’s the Limit! conference put on by the New York City, Westchester, and Manhattan branches of the American Association of University Women. This conference is open to 7th grade girls from New York City and Westchester schools and is designed to encourage girls to pursue science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) careers through fun, hands-on activities and by providing them with women role models from these fields. This conference has been run annually in the New York City area since 2004, first at Barnard College and now at the College of Mount St. Vincent, and is based on the Expanding Your Horizons in Science and Mathematics™ (EYH™) conferences, which first started in 1976 and now take place worldwide. During the conference, the girls hear a keynote address and then break up into smaller groups to do two hands-on workshops.

I led a workshop called ‘Flower Hour,’ which explored the science of a flower’s shape. I brought in five different types of flowers for the girls to examine. First, I asked the girls to look carefully at a yellow tulip, to describe what they were seeing in as much detail as possible. I gave them five minutes to write their observations down, and then they took turns sharing them with the group. I was impressed with the responses: One girl knew that the plant from which the flower came was an autotroph, an organism which makes its own food from inorganic compounds, and another observed that the flower had the same number of petals as it did stamens. After each girl shared her observations with the group, I drew a flower on the board and taught them the botanical names for floral parts.

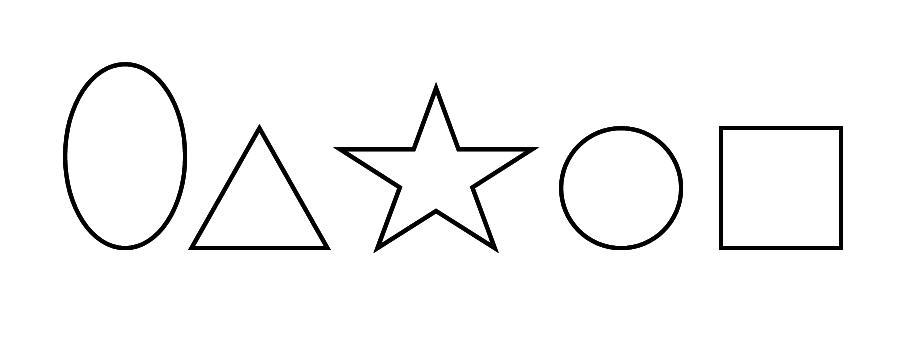

In preparation for our next activity, I put five shapes on the board: an oval, a triangle, a star, a circle, and a square.

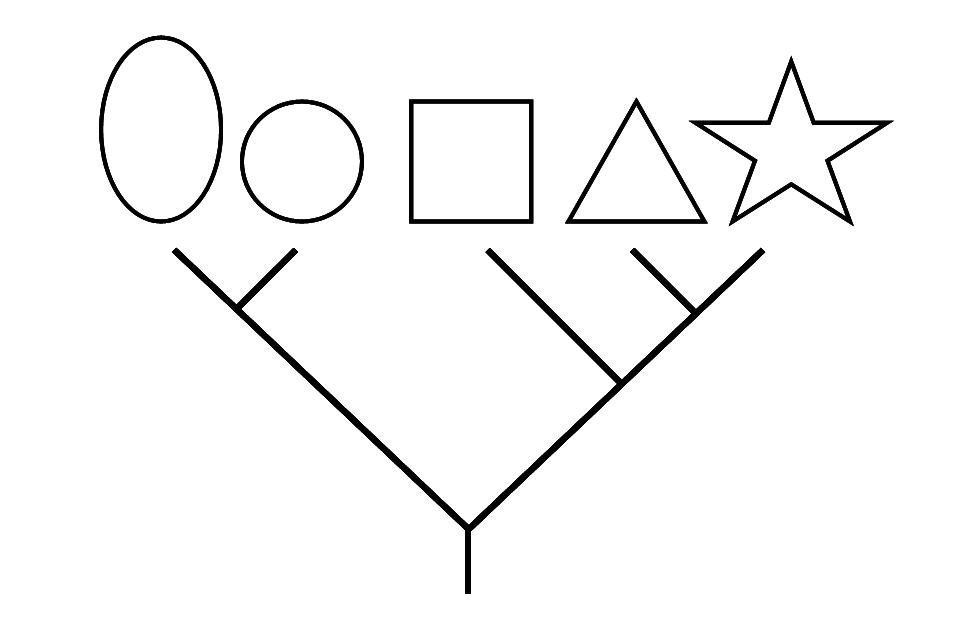

I asked the girls how they would group these shapes. Everyone agreed that the circle and oval belonged in one group and the triangle, square, and star belonged in another because circles and ovals have rounded edges and triangles, squares, and stars are pointy. Then I asked them, of the triangle, square, and star, which two were more closely related? There were some differing opinions, but they were all backed up by good reasoning. Some girls thought the triangle and square should go together because a square is made up of two triangles, whereas others thought that the triangle and star were more closely related because a star’s points look like triangles. From these series of groupings, we could create a family tree of these shapes, which shows how the shapes are related to each other.

Next, I gave each pair of girls five different flowers: a yellow lily, a pink lily, a yellow tulip, a red and yellow tulip, and a yellow freesia. I asked them to observe the similarities and differences among the flowers that would allow them to group them in a way that reflects how the flowers are related to each other, like we did with the shapes. I chose these particular flowers for several reasons. The duplicate lily and tulip flowers differed only in color, so were easily grouped as similar based on form and shape. I chose three different types of yellow flower to illustrate that some characteristics are more useful in determining relationships than others. In this case, three flowers share the same color, but have different shapes; therefore, grouping according to shape instead of color gives a more accurate estimation of the relationships among the flowers.

The girls noticed that the lilies and tulips all had six colorful tepals, the term given to the showy, petal-like structures of flowers whose sepals and petals look similar. The freesia, on the other hand, had green sepals and six petals, but the petals were fused to form a tube, which distinguished this flower from the others. The girls also observed that the carpels, the female flower parts, of the lilies and tulips looked similar, whereas that of the freesia was much more delicate and had a different shape. In light of these observations, the girls grouped the tulips and lilies together, while the freesia stood alone as distinct from the rest. Through this exercise, the girls not only learned to closely examine flowers and their specific parts, but also about studying evolution and how shared characteristics can be used to determine the relationships between species. The family tree the girls created was correct. Lilies and tulips are both members of the Liliaceae, the lily family, whereas freesias belong to the Iridaceae, the iris family.

Overall, it was an excellent day. I got to interact with very bright, engaged young women who were inquisitive and eager to learn. They will now look at flowers in a new way, appreciating not only their beauty, but also how scientific observation can be used to estimate the evolutionary relationships between species. I hope that my enthusiasm and love of science and plants promoted their interest in the sciences and encouraged them to view a scientific career–maybe even botany!–as a plausible option for their future. I am already looking forward to next year’s conference!