Microscopic Marvels: The Exquisite Shapes and Structures of Fern Spores

Posted in Interesting Plant Stories on October 23, 2013 by Robbin Moran

Robbin Moran is the NYBG‘s Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, with a specialty in ferns. His field work takes him primarily to the American tropics, especially Central America and the Andes Mountains. Among his many publications is the general-interest book “A Natural History of Ferns” (Timber Press).

A wonderful aspect of botanical research is observing the amazing structures produced by plants. An example in my research is fern spores. These are single cells released by the millions from the undersides of fern leaves. They are picked up by air currents and carried away from the parent plant, thus dispersing the species. They function like seeds, but, unlike seeds, they are single-celled and lack an embryo and seed coat, both of which are multi-cellular structures.

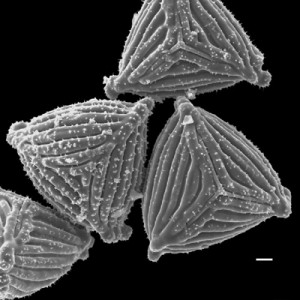

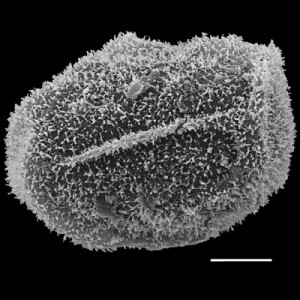

As part of my research, I study fern spores with the Garden’s scanning electron microscope, or “SEM” for short. To the naked eye, spores appear as dust. Most are 30–50 micrometers long, a micrometer being one one-thousandth of a millimeter. By comparison, the average width of a human hair is about 70 micrometers. For reference, the white bar in each photo here equals 10 micrometers. Because the spores are so small, the SEM’s high magnification and resolution are exactly what is needed to reveal their surface details, which are often exquisite and valuable in scientific classification. These details are often so distinct that they distinguish different families, genera, or even closely related species.

One helpful character in classification is the shape of the germination furrows. They are either Y-shaped (trilete; Photo 1) or a single straight line (monolete; Photo 2). These furrows indicate where the spore was attached to three other spores immediately after they were produced by cell division. When the spore germinates, its contents protrude through the markings.

Besides monolete and trilete markings, fern spores exhibit many other kinds of surface details, such as a ridge around their outer margin, or equator (Photo 3). Others bear long spines (Photo 4). No one is sure what, if any, advantage these structures lend to the plant. There are other types as well, some of which I will show in the future.

I have been listening to Robbin talk about ferns for some eleven years, It is always as interesting as this, an exercise in knowing something unlike us really well, which, I think, makes pteridologists and even amateur fern lovers generous and tolerant. But then, I’m a poet.