Katharine Brandegee: Blazing a Trail for Women in Science

Posted in Past and Present on February 3, 2014 by Amy Weiss

Amy Weiss is a curatorial assistant in The New York Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, where she catalogues and preserves plant specimens from around the world.

Novels are full of unconventional women, from Jane Austen’s spunky Elizabeth Bennet to the brilliant botanist Alma Whittaker in Elizabeth Gilbert’s recent novel The Signature of All Things. But Mary Katharine Layne Curran Brandegee (1844-1920), a real-life botanist, could certainly have taught these fictional women a thing or two about forging your own path.

Born Mary Katharine Layne in 1844 to a Tennessee farmer, she was a young girl when the Laynes moved west to California during the 1849 gold rush, eventually settling in Folsom, California. She married Hugh Curran, a constable, in 1866, but he died of alcoholism in 1874. Often described as strong-willed, Mrs. Curran moved to San Francisco the following year and enrolled at the University of California’s medical school. She was only the third woman to do so.

At that time, botany was an essential component of medical science education, and after receiving her degree, Curran followed the advice of an instructor and pursued botany rather than practice medicine. She became a member of the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco in 1879, continuing her botanical training by collecting plants throughout California and working in the Academy’s herbarium. In 1883, Curran was appointed a curator of botany, one of the first women to hold such a position at a major museum, and in 1891 she became the sole botanical curator.

In 1885, Townshend S. Brandegee (1843–1925), a civil engineer by trade but an avid plant collector, arrived in San Francisco and became an active member of the Academy. As Curran wrote in a letter to her sister, she fell “insanely in love” with Brandegee, and the two were wed in 1889. For their honeymoon, they walked from San Diego to San Francisco, a distance of 500 miles, collecting plants along the way.

Katharine Brandegee went on to mentor another woman, the Colorado botanist and former schoolteacher Alice Eastwood, even giving up her salary so that the Academy could hire Eastwood as a co-curator. In 1894, the Brandegees relocated to San Diego, where they set up their own herbarium and botanical garden. They returned to the Bay area shortly after the 1906 earthquake destroyed most of San Francisco and the Academy’s herbarium, working out of the herbarium at the University of California, Berkeley, to which they donated their personal herbarium of more than 76,000 specimens. Katharine Brandegee died in Berkeley in 1920, but her contributions to science live on through her writings and collections.

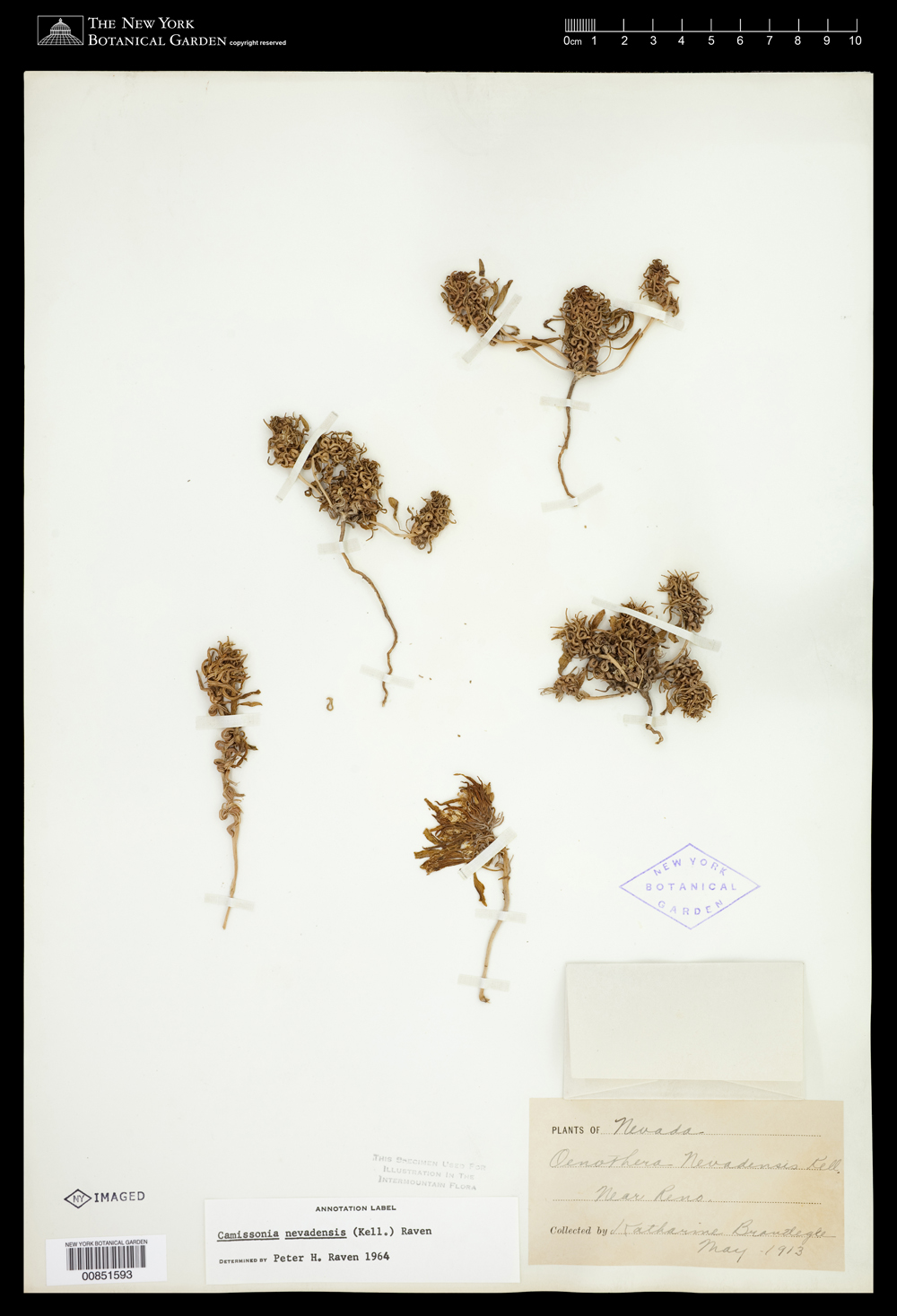

This specimen from the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium neatly shows the history of the California Academy of Sciences and its ties to the New York Botanical Garden. The specimen was collected by Katharine Brandegee. The species was later moved to the genus Camissonia by Peter Raven, a prominent botanist who was first encouraged by Alice Eastwood, Brandegee’s former student. This specimen was later used to illustrate the species in the multivolume Intermountain Flora, published by the NYBG Press, which is one of the major accomplishments of the husband-and-wife team of Botanical Garden scientists Patricia and Noel Holmgren.

Brandegee portrait courtesy of Berkeley.edu

Source: Daniel, T. F. 2008. One hundred and fifty years of botany at the California Academy of Sciences (1853-2003). Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci., ser. 4, 59: 215–305.