The Amazing Feat of Jeanne Baret

Posted in Nuggets from the Archives on March 12, 2014 by Elizabeth Kiernan

Elizabeth Kiernan is a project coordinator for the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium at The New York Botanical Garden. She is currently working on a program to document the biodiversity of the Amazonian region of South America. Each Wednesday throughout Women’s History Month, Science Talk will celebrate one of the many women of science to have left a mark on botanical history.

Jeanne Baret risked everything for her love of botany and, in doing so, became the first woman to circumnavigate the globe. This notable feat was even more remarkable because for much of the voyage, her shipmates did not know she was a woman.

Baret was born in France in 1740. Her working-class parents taught her to identify plants for their healing properties, and she became an expert “herb woman,” a peasant schooled in botanical medicine. Her passion for botany drew her to renowned naturalist Philibert Commerson, who shared her fascination with plants.

Through the recommendation of Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist who devised the system for naming species that science still uses today, Commerson was hired as the botanist on Louis de Bougainville’s voyage around the world in search of undiscovered territories, which set sail in 1766.

Commerson wanted Baret to join him in identifying and collecting plant species because of her vast botanical knowledge, but at this time women were strictly prohibited from sailing aboard French ships. Baret and Commerson devised a plan so that she could join the expedition as Commerson’s field assistant: disguise Jeanne as “Jean” by wrapping bandages around her chest and dressing her in loose-fitting clothing to hide her gender.

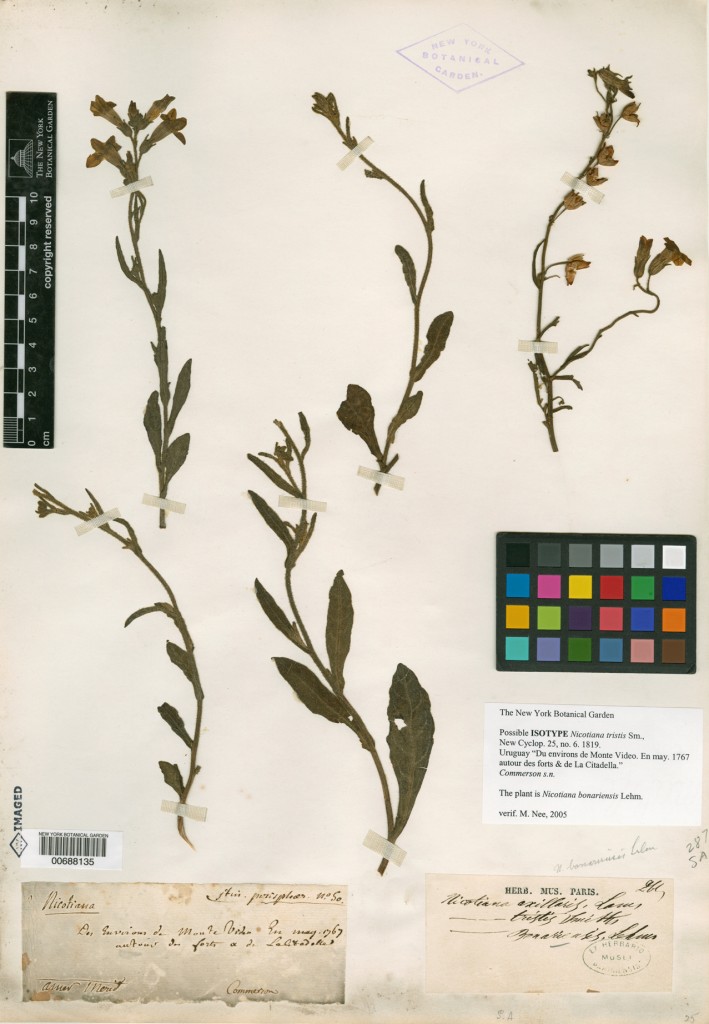

On the expedition, Baret had to endure physically demanding work in the field, including carrying the heavy, cumbersome wooden plant presses used to preserve botanical specimens. She was involved in collecting more than 6,000 plant specimens on the voyage, though she was never credited. Commerson was frequently incapacitated due to poor health, and at these times Baret led the expedition as chief botanist. She made some of the more notable collections of the expedition; in fact, she probably deserves credit for the greatest find, Bougainvillea brasiliensis, a vine with bright, beautiful flowers that is native to South America.

After passing as a man for some two years, Baret’s true identity was discovered, possibly by tribesmen in Tahiti. Surprisingly, she was not prosecuted, likely because expedition commander Bougainville was so impressed by her contributions in the field. She and Commerson, however, were forced to leave the expedition at the French colony of Mauritius. Commerson died there, and eventually Baret married a French soldier. It was only in 1774 or 1775, when the couple returned to France, that she completed her voyage around the world.

The Prince of Nassau-Siegen, a nobleman who was also part of Bougainville’s expedition, noted Baret’s accomplishments. “I want to give her all the credit for her bravery,” he wrote in his memoirs. “She dared confront the stress, the dangers, and everything that happened that one could realistically expect on such a voyage. Her adventure, should, I think, be included in a history of famous women.”

Although she did not receive credit for her findings at the time, Baret was finally given the recognition she deserved when a new South American species in the potato-tomato family, Solanum baretiae, was named in her honor in 2012.

To learn more about Jeanne Baret, you can read a biography of her life, The Discovery of Jeanne Baret: A Story of Science, the High Seas, and the First Woman to Circumnavigate the Globe, by Glynis Ridley.

It is true that Jeanne Baret was a brave pioneering woman who was not properly credited for her work. However Ridley is not the source to go to for information. The best source I have seen is “Jeanne Baret..” by Henriette Doussourd. Moulins. 1987. Also “Monsieur Baret..” by John Dunmore. Heritage Press (NZ). 2002. is reliable. In recent years Nicole Crestey, a researcher in Réunion, has published a couple of good articles on the Internet.

Ridley failed to find many of the key sources (see reviews by Knapp in Nature Magazine Feb 3, 2011 and Helferich in the Wall St Journal Jan 24, 2011) and introduced many clear errors as well as wild speculation. Unfortunately this has distorted your article. For example, in the sentence starting “Her working class parents..” and the next sentence you make three statements but I have never seen any evidence for any of these three. They were all wild speculation by Ridley.

Sadly your article continues in the same vein.

Mark Gimson.