Documenting Plant Diversity: Using a Flora to Describe Flora

Posted in Applied Science on February 20, 2015 by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori, Ph.D., is a Curator Emeritus associated with the Institute of Systematic Botany at The New York Botanical Garden. His research interests are the ecology, classification, and conservation of tropical rain forest trees.

Among the many products of the research published by scientists at The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) are Floras. A Flora is a book in which species are described, while the word flora refers to the totality of plant species in an area; in other words, a flora is described in a Flora.

Floristic publications document and describe the diversity of a given group of plants growing in specific geographic areas. They may be floras of algae, mosses, ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms or combinations of these groups. For example, a Flora might include all of the vascular plants (ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms) of the northeastern United States. The equivalent of a Flora for fungi is called a Mycota, because fungi are more closely related to animals than they are to plants.

Some examples of Floras are the Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada by Henry A. Gleason and Arthur Cronquist, the Intermountain Flora recently completed by Noel and Patricia K. Holmgren and their colleagues, and Pleurocarpous mosses of the West Indies by William R. Buck–all published by The New York Botanical Garden Press. Floras are important because they allow both amateur and professional botanists to identify plants—the first step in developing a deeper appreciation of plants and for carrying out research on them. In addition, scientific Floras or Mycotas serve as the basis for field guides such as Roy Halling and Gregory M. Mueller’s Common Mushrooms of the Talamanca Mountains, Costa Rica.

Floristic and Mycota projects take years and sometimes decades to complete. Guide to the Vascular Plants of Central French Guiana, which I co-authored, consumed 11 years and required the participation of 80 botanical specialists to complete, and the Intermountain Flora engaged many botanists for over four decades until the last volume was published in 2012. The time needed to gather the specimens upon which Floras and Mycotas are based is one of the reasons that floristic and mycota projects are so time-consuming.

It is difficult to determine when the botanical exploration necessary for writing a Flora or a Mycota has gathered enough collections to make the inventory as complete as possible. Tropical Floras, such as our French Guiana Flora, are out-of-date at the time of publication because new species are discovered, species already described but new to the area are collected, and new information about known species is gathered. Publishing too early makes the Flora so incomplete that it becomes difficult for users to identify the plants they find.

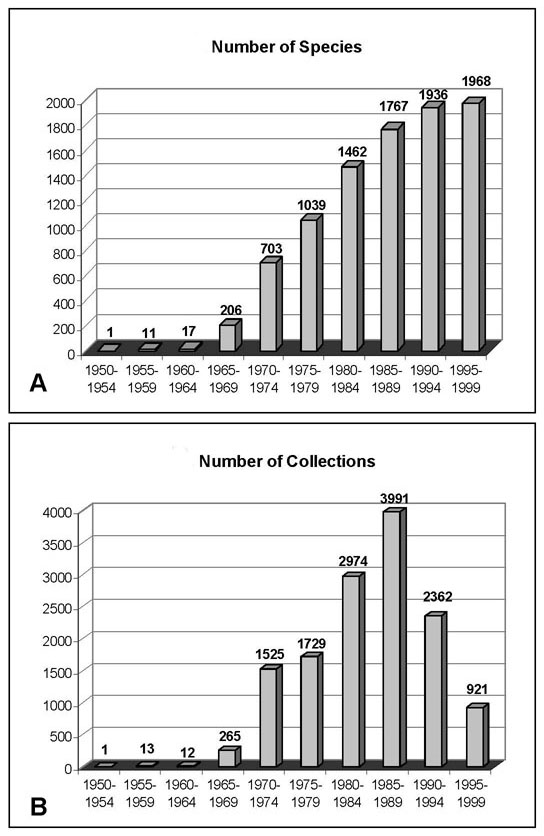

To determine the time to publish the central French Guianan Flora, my co-authors and I made a graph to demonstrate how many new species for the Flora were gathered on each new expedition. When the graph leveled off, we finished the manuscript and published the Flora. We also prepared a graph that showed that the collections made were fewer on later expeditions in comparison with those made on earlier expeditions. This was because over time we had collected most of the common species and, thus, had to work harder to find species we had not yet inventoried. If a species could possibly be new to the Flora, we were willing to spend hours collecting the specimens needed to add that species to our Flora!