Plants from Mt. Elbert: Life on the Rocky Mountains’ Highest Peak

Posted in Interesting Plant Stories on March 26, 2019 by Sarah Dutton

Sarah Dutton is the Lead Digitizer for the Southern Rockies Digitization Project at The New York Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium.

The New York Botanical Garden is currently digitizing all of its herbarium specimens from the Southern Rocky Mountains, a major subregion of the Rockies that runs from southern Wyoming through Colorado to northern New Mexico and eastern Utah. As the information enters our database, we are learning more about the nuances of our collection. Recently, I decided to see if we have any specimens collected from the alpine zone of the tallest mountain in all of the Rockies—Colorado’s Mt. Elbert (elevation 14,440 feet). As it turns out, we have 32 specimens from Mt. Elbert, most collected before 1920. Our oldest dates from the 1873 Hayden Geological Survey, and 20 of the specimens were collected in the alpine zone, at 11,000 feet or above.

Alpine tundra occurs where it is too cold for trees to grow because of high elevation. The elevation where trees cease to grow varies with latitude and microclimate, but in Colorado, it tends to happen between 11,000 and 11,500 feet. Here, plants have evolved many fascinating adaptations to exposure to strong winds and cold temperatures. For example, many alpine plants have hairs covering their leaves and stems. This traps warmer air and moisture next to the plant tissues, protecting them from cold and reducing the water loss caused by wind. Many of the plants collected from Mt. Elbert display this adaptation, such as specimens of Smelowskia calycina (alpine false candytuft), Erigeron pinnatisectus (feather-leaf fleabane), and Draba aurea (golden draba). Another common feature of these plants is short stature, which is advantageous because the air is warmer closer to the ground.

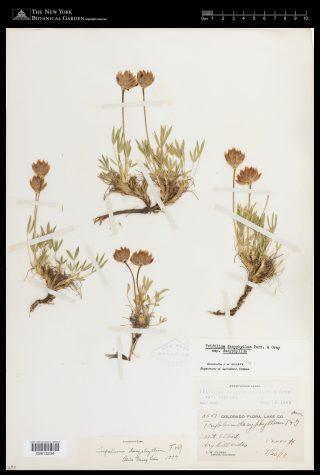

Alpine plants have to contend with a short growing season, the period of time when conditions are warm enough for plant growth. This is because cold temperatures slow down some of the reactions involved in photosynthesis, limiting the amount of energy available to the plants. Even during July, the average temperature on Mt. Elbert is only 55 degrees Fahrenheit, and there may be days with temperatures below freezing. On one specimen sheet dated July 23, 1877, the collector notes that the plant, which was in flower, was found “near snow.” This short growing season is one reason that most alpine plants are perennial. Perennials do not have to start growing from seed each year and can store energy from multiple growing seasons. This relieves the pressure to reproduce every single year. Some perennial alpine plants begin to form flower buds years in advance of their blooming. Trifolium dasyphyllum, or alpine clover, is one example of a perennial from our herbarium collection.

As we continue to digitize specimens for the Southern Rockies Digitization Project, even more interesting specimen data will become searchable in our database and the C. V. Starr Virtual Herbarium. Though I have never been to the Rocky Mountains myself, the images and data we have produced so far have allowed me a small glimpse into the fascinating world of the alpine tundra.