The Herbarium: Primary Data Source for Biodiversity Research

Posted in Science on December 15 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Barbara Thiers, Ph.D., is Director of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium and oversees the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium. |

Part 2 in a 3-part series

Read Part 1

Worldwide trends notwithstanding, the chief concern of our William and Lynda Steere Herbarium management team on a daily basis is not the decline in the use of natural history collections, as reported in a New York Times article this summer, but rather how to keep up with the needs of all our users.

Worldwide trends notwithstanding, the chief concern of our William and Lynda Steere Herbarium management team on a daily basis is not the decline in the use of natural history collections, as reported in a New York Times article this summer, but rather how to keep up with the needs of all our users.

Scientists use the Steere Herbarium to answer the most critical questions about plant diversity, namely: How many species are there? How are they related to one another? What environmental factors control their growth? Given that plants supply most of the food, fuel, shelter, and medicines for the earth’s population, predicting how these organisms may respond to climate change is one of the most pressing questions for scientists today.

Visitors are sometimes surprised that most of the scientists who use to the Herbarium are still doing the fundamental work of documenting the Earth’s biodiversity. “Don’t we know all the species yet?” some have asked. The answer is “No, not by a long shot.” Estimates are that we know only about 75 percent of the world’s plant species and less than 10 percent of the species of the fungi, the two major groups of organisms represented in the Herbarium collections.

Biodiversity scientists usually endeavor to fill these still very large knowledge gaps in one of two of ways. Some approach the problem from a geographical perspective, documenting all the plants and fungi of a particular area, producing a work known as a flora. Some take a taxonomic approach, documenting all members of a group of related organisms, resulting in a work known as a monograph.

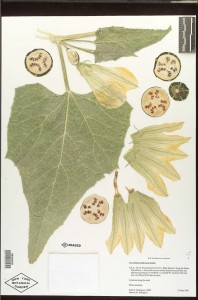

Regardless of the approach, there are common elements to the resulting synthesis. To be properly documented, each species must have a description of its physical characteristics, one or more illustrations, and a characterization of its habitat. Each treatment must present a comparison of the characteristics of all included taxa, usually in a device known as a key, which allows the identification of unknowns. For monographs, the researcher must also extract DNA and compare the sequences of particular genes in order to position each species on an evolutionary tree. Scientist get the information needed for these syntheses from the published literature, their personal observations of living organisms, and most importantly, herbarium specimens. The more specimens a scientist examines, the more robust his or her descriptions and keys will be.

The collections of the Steere Herbarium have contributed to just about every major study of biodiversity in the Western Hemisphere during the past century—in the past year alone, at least 262 published floristic or monographic works cited specimens from the Steere Herbarium.

A visitor once asked me, half-teasing, “But do you really want for all the plants in the world to be known? Wouldn’t you folks be out of a job? Who would need a herbarium then?” Truly, we might be a little sad to reach the point where there were no more new species to be discovered. However, there are many other questions that herbaria can help to answer, such as why plants and fungi grow where they do, and how and why Earth’s vegetation has changed over time. Such information is critical to understanding Earth’s critical ecosystems to preserve human health.