Leopold’s Land Ethic

Posted in Science on April 11 2013, by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori is the Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany at the The New York Botanical Garden. His research interests are the ecology, classification, and conservation of tropical rain forest trees. His most recent book is Tropical Plant Collecting: From the Field to the Internet.

As a student in Botany at the University of Wisconsin in the early 1970s, I became aware of Aldo Leopold’s land ethic philosophy. In A Sand County Almanac he wrote:

As a student in Botany at the University of Wisconsin in the early 1970s, I became aware of Aldo Leopold’s land ethic philosophy. In A Sand County Almanac he wrote:

“This sounds simple: do we not already sing our love for and obligation to the land of the free and the home of the brave? Yes, but just what and whom do we love? Certainly not the soil, which we are sending helter-skelter down river. Certainly not the waters, which we assume have no function except to turn turbines, float barges, and carry off sewage. Certainly not the plants, of which we exterminate whole communities without batting an eye. Certainly not the animals, of which we have already extirpated many of the largest and most beautiful species. A land ethic of course cannot prevent the alteration, management, and use of these ‘resources,’ but it does affirm their right to continued existence, and, at least in spots, their continued existence in a natural state. In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.”

Although written in 1949, Leopold’s land ethic is more important today than it was then. If environmental destruction was bad then, what would he think today? During his time the world’s population was only 2.5 billion whereas today it is over seven billion! In addition, the increase in per capita consumption throughout much of the world, as well as the giant leap in mankind’s technological ability, have created an even greater capacity for Homo sapiens to destroy life on Earth. Thomas Friedman reminds us in his book Hot, Flat, and Crowded that “We are the only species in this vast web of life that no animal or plant in nature depends on for its survival—yet we depend on this whole web of life for our survival.”

Two articles in the New York Times, each released in the third week of March, suggest that Leopold’s land ethic has not been embraced by most of the world. Although these articles deal with two iconic animals, their fate is directly or indirectly linked with the plants they depend on, and vice-versa. Thus, in order to protect animals, the plants associated with them must also be protected.

In the first article written by Lincoln Brower and Homero Aridjus, “The Winter of the Monarch,” documents the precipitous decline of monarch butterflies, well-known in eastern North America for their beauty. However, the species is also famed for the 2500-mile migration that thousands of monarchs undertake, traveling from an area east of the Rocky Mountains to a small region in the mountains of Mexico where the butterfly overwinters; the species is also frequently highlighted in biology classes as a prime example of insect metamorphosis.

Unfortunately, monarch butterflies are declining in number because their overwintering areas in Mexico are being decimated by logging, as pointed out in the article: “Today the winter monarch colonies, which are found west of Mexico City, in an area of about 60 miles by 60 miles, are a pitiful remnant of their former splendor. The aggregate area covered by the colonies dwindled from an average of 22 acres between 1994 and 2003 to 12 acres between 2003 and 2012. The size of the area this year hit a record low of 2.9 acres.” Logging combined with butterfly mortality caused by agricultural pesticides and herbicides creates a dim future for the success of the monarchs. These butterflies depend on plants for their survival—the fir forests they overwinter in, the milkweeds their larvae eat, and the nectar-producing plants the adults depend upon for food.

The second article, entitled “Slaughter of the African Elephants,” was written by Samantha Strindberg and Fiona Maisels. These conservation biologists describe the precipitous 62 percent decline in numbers of African forest elephants between 2002 and 2011. Although much of this drop in population can be attributed to deforestation, poaching for elephant tusks used to make ivory trinkets plays a major role in pushing these elephants toward extirpation in much of their range. This cruel slaughter is especially disturbing for the fact that the elephants are killed for their ivory, a material used to make objects of no essential utility to humans. The demise of elephants also negatively impacts some plants because many species depend on these large, grazing mammals to disperse their seeds.

If iconic animals such as the African elephants and monarch butterflies are inexorably being driven to extinction, how many lesser known animals and plants are facing the same fate? How many canaries in the coal mine have to die before humans take their heads out of the sand and stop the senseless slaughter of life on Earth? Mankind desperately needs to follow and transmit Leopold’s land ethic to future generations, because if iconic animals are exterminated, our planet will become a very boring, unhealthy, and lonely place to live.

A Sand County Almanac cover courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

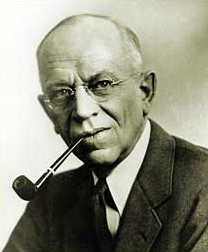

Aldo Leopold portrait courtesy of LeopoldHeritage.org.