The Diary of H.H. Rusby: Into Peru

Posted in Science on June 15 2013, by Anthony Kirchgessner

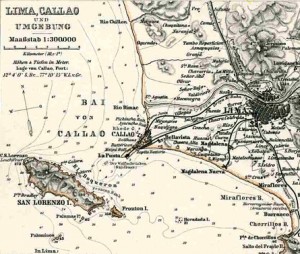

Now in week three, Henry Hurd Rusby‘s Mulford Expedition arrives in Peru after passing through the Panama Canal. Anchoring in Callao, several of the expedition’s number travel on to Lima as guests of the Peruvian leadership. Gathering medicines, touring the capital, and meeting with newspaper representatives are the orders of the day, yet the trials of surviving abroad play out even in the relative safety of urban Peru.

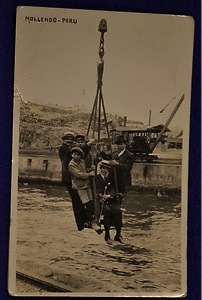

Reboarding the Santa Elisa, the expedition steams southeast to Mollendo where the competitive business of hotel porterage and questionable exchange rates preface the expedition’s journey into higher altitudes. There Rusby’s talents as a botanist are finally put to use identifying cacti, mountain trees, and local vegetables on the road to Arequipa.

OFFICIAL DIARY of the MULFORD BIOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF THE AMAZON BASIN

H. H. RUSBY, DIRECTOR

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 15, 1921

The swell was very heavy this morning, but toward noon we got close to shore and were more comfortable. About noon we anchored at Callao, and quickly went ashore. Dr. Granier, Lima’s leading surgeon, took us ashore in the launch of the President’s son, who is chief of Peru’s Aviation service. We also went from Callao to Lima in the private trolley car of this official. Mr. Motte, the representative of the Mulford Company, reached the ship just after we had left it. My chief business in Lima was to procure some additional medicines, which I find are likely to be needed.

We had intended to return to the ship this evening, but there were so many places and people to be seen, especially newspaper representatives, that we decided to stay at the hotel in Lima. In the evening Mr. Motte entertained us at dinner at the Zoo Restaurant.

THURSDAY, JUNE 16, 1921

Today, Dr. Hoffman accompanied Dr. Granier to visit the hospitals while the rest of us went to the natural history museum and the Zoo, and also visited the market. At noon we met the representative of the “CHRONICAL” newspaper and had our picture taken in a group. We were notified by the Steamship Company that the ship would sail at five o’clock, and so hastened on board, but only to find that it would not sail till the following afternoon. We had Mr. Motte at dinner on board.

I secured all the medicines that I needed and Dr. Granier sent us a copy of Waring’s Surgery, in English, something that I greatly needed.

FRIDAY, JUNE 17, 1921

I decided not to go ashore today, but to get my trunk and suitcase repacked, ready to go ashore at Mollendo, as I shall probably be decidedly under the weather en route to the place, the sea being very rough here. This was done very satisfactory before noon, and I wrote up my diary for the last few days, and balanced my accounts for the last.

Mr. Mann went ashore, and I asked him to investigate a story that the railroad from Arica to La Paz is interrupted, so that the freight cannot be transported. So far as can be learned, there is no truth in the report.

Our steamer got away this evening and I found the sea distressingly rough.

SATURDAY, JUNE 18, 1921

This has been the most difficult day of the entire journey for me, as the swells were very high and I was obliged to keep on my back nearly all of the time. In the middle of the afternoon I had to go to bed and so missed the complimentary dinner with special menu, which the captain had arranged for our party.

SUNDAY, JUNE 19, 1921

We landed at Mollendo before noon. The waves were heavy, and the trip ashore in the launch was very trying. We were raised to the top of the wall in a huge chair by a crane. Mann and McCarty came ashore with me. Hoffman left his trunks on board, and had to send back after them. Out trunks were left in the custom house till the next day, but we were permitted to take our hand baggage to the hotel with a very slight examination. Porters carry the baggage on their shoulders and they extract as much money as the laxity or ignorance of the passenger will permit. Thus one passenger would pay three times as much as another for the same service. The only way to be safe is to take time to arrange every detail, and to price before permitting them to take anything. Count the pieces of baggage, point them out and agree on the price. If not satisfactory, get another porter. Finally set down on a piece of paper the number of pieces, their destination and the price and give it to the man. When paytime arrives, pay strictly according to this paper.

We landed at Mollendo before noon. The waves were heavy, and the trip ashore in the launch was very trying. We were raised to the top of the wall in a huge chair by a crane. Mann and McCarty came ashore with me. Hoffman left his trunks on board, and had to send back after them. Out trunks were left in the custom house till the next day, but we were permitted to take our hand baggage to the hotel with a very slight examination. Porters carry the baggage on their shoulders and they extract as much money as the laxity or ignorance of the passenger will permit. Thus one passenger would pay three times as much as another for the same service. The only way to be safe is to take time to arrange every detail, and to price before permitting them to take anything. Count the pieces of baggage, point them out and agree on the price. If not satisfactory, get another porter. Finally set down on a piece of paper the number of pieces, their destination and the price and give it to the man. When paytime arrives, pay strictly according to this paper.

We went to the Grand Hotel, where the meals were good, and were eaten in a pleasant, cool veranda, surrounded by lovely flowers.

Being Sunday, no business could be done, and we spent the day walking about, clearing up accounts and planning for the morrow. The train will leave at 12:30 P.M. and we shall have much to do. My key does not work on my suitcase and I cannot get my clean clothing. Wrote a letter to Margaurite.

The water here is said to be very bad and we use bottled water and weak coffee and tea.

MONDAY, JUNE 20, 1921

I rose early and had “disayuna” [sic] (breakfast) but would not be content with coffee and bread. I made them cook ham and eggs, with butter for my bread and cheese afterward. When I was very well contented [sic]. Hunted up a so-called locksmith to open my suitcase but he failed in the attempt.

Visited the market but found nothing new or of special interest.

Went to the bank and inquired the rate of exchange, which was $3.62 for a Peruvian pound, of ten dollars. The bank was not open till 9:30 A.M. At this time I returned and was told that the rate was over $4.30! At another place it was $5.00, at another $3.92. This is the same as all other business; the stranger is to be swindled to the full extent of the possibilities. I got along with what Peruvian money we could make up among us, and await Arequipa for further exchange.

Went to the office of Danelsberg, Ewel & Company, and introduced myself and arranged for the transaction of shipments. Obtained a letter to their La Paz branch.

Two American ladies who came on the ship are going to Cuzco, and I have been of much service to them, although they are careful to do everything possible for themselves.

Dr. Hoffman, like many learned men, is not practical. He can be imposed on by everyone and he speaks no Spanish and is innocent of the ways. He is very nervous and easily “rattled” and I shall have to look out for him.

We got our things dispatched at the custom house without any trouble and secured passage on the railroad. Were told that it would be cheaper to get 15 day tickets through to La Paz, with stopover privilege, and did. So this ticket costs $54.40 without baggage. I sent three pieces of baggage to Arequipa. This weighed 75 kilos (165 lbs.) and cost $6.75 soles. Two pieces sent to La Paz weighed 100 kilos, of which 70 were free, the remaining 30 kilos costing $7.30 soles. Hoffman had 168 kilos to pay for and 70 free, equaling 523 lbs.

We left promptly at 12:30, the road runs for some distance along the shore, when the surf is rough it is magnificent. Soon we saw a magnificent field of cotton. We traveled many miles over perfectly bare hills. At exactly 1000 feet altitude, we saw some fine cactuses, with some hardy Compositae and (apparently) heliotropes. The finest cactuses are tall, branching from the base, columnar forms, and often some low, widely branching ones, covered with long, coarse white spines, apparently a cylindrical Opuntia. The former grow larger as we ascended. Soon we saw white fig-trees, 20 feet high, with trunks a foot in diameter. Here the rock crevices were covered with green moss. At 2100 feet, we see very fine closely prostrate plants, apparently an Enphocbris. Then come large-flowered Vigineras or Eucilios. The abundance of dead stems indicate a rich vegetation at an earlier season.

In deeply shaded nooks, where one can scarcely get a glimpse, grow a shrub with elongated scarlet flowers. At 3000 feet it became very barren, even the cactuses disappearing. The rocks are covered with a very fine close grey lichen. At 3300 feet we come in sight of snow-capped mountains.

My systolic blood-pressure, before leaving Mollendo, was 130. At three thousand feet it was 120.

For many miles we traversed a table-land, the ground barren of all vegetation. The snowy mountains were magnificent. Toward the farther side of this table-land are many sand-dunes, of a peculiar grey color, which evidently shift with the wind. At 5000 feet we encounter a few columnar cactuses, smaller than those before seen and apparently of a different species.

At length we begin descending into a deep valley with a tree lined river at the bottom. It is the Guila, on which Arequipa is located, and we are soon running up along its banks. At about seven o’clock we arrived at the station.

Dr. Hoffman has taken the blood-pressure of myself and Mrs. Haines at different elevations. On arrival at Arequipa the record shows a steady and marked decrease in mine, while hers shows a slight increase. I have suffered somewhat from “soroche” but she has not.

Dr. Hoffman and I went to the Hotel Castro, while the ladies went to the Quinta. All except myself expected to go to Cuzco on Wednesday, I going to La Paz on Friday. I retired early, being pretty tired, but was routed out by a note from the ladies asking me to go to the office to meet them. They then informed me that they must leave for Cuzco at seven-thirty tomorrow morning and they needed assistance in making their arrangements. This I succeeded in rendering them and it then became necessary for me to find Dr. Hoffman and inform him of the change, which I did.

TUESDAY, JUNE 21, 1921

We were up before six this morning preparing for the railway journey of my friends. They got off promptly at seven-thirty after which I visited the city market, a most interesting place. Among the interesting vegetable products seen was a variety of “pepino”, the fruit of Solanum muricatum, of a green color with dull-purple stripes. When I first saw this fruit in Lima in the month of January, it was of an ivory-white color with rich purple stripes. I inquired about this variation, and was told that it was due to the season, this being the winter and January the summer. I went to the hotel and occupied myself in letter writing and fixing up my accounts.

Callao header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.