“Message Plants” in the Communications Age

Posted in From the Field on November 22, 2017 by Science Talk

Gregory M. Plunkett, Ph.D., is Director and Curator of the Cullman Program for Molecular Systematics at The New York Botanical Garden and Michael J. Balick, Ph.D., is Vice President for Botanical Science and Director and Philecology Curator of the Botanical Garden’s Institute of Economic Botany.

The people of Vanuatu, an island group in the South Pacific Ocean, have a rich cultural history and intense desire to maintain these cultural practices as living traditions, enshrined in the concept of kastom. However, preserving kastom can be a great challenge in a rapidly changing and globalizing world. We initiated a biocultural conservation program in Vanuatu’s southernmost islands, the area known as Tafea Province, aimed at understanding the area’s plant and fungal biodiversity and its local uses, both traditional and modern. This initiative is helping to conserve biodiversity resources and support cultural practices in this remote part of the world.

To begin the project, we held extensive meetings with community members to gauge their interest in participating in the documentation of plants and plant uses. In many areas, we saw signs of rapid erosion of such knowledge, where grandparents knew the traditional information, but their children and even more so their grandchildren had experienced a growing alienation from the natural world, especially as they became more dependent on modern approaches to life.

The younger generation, for instance, understands the importance of mobile phones for conveying information. But in the traditional life of the people of Aneityum, the southernmost island of Vanuatu, it was plants that played a critical role in communication. Local people generously shared their knowledge about this topic.

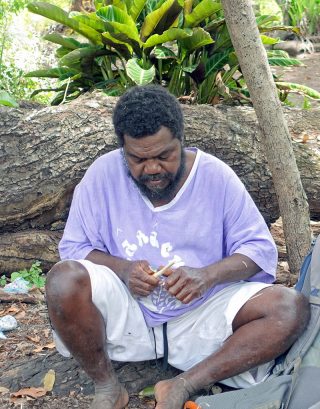

For example, Reuben Neriam told us that traditionally it was considered disrespectful to deliver news of an important event, such as a birth or death, by telling another person directly what had happened. Instead, the bearer of good or bad news would find a stick from a particular plant species, cut it into small pieces (about a foot long), and place them at the entrance of the house of the other person. Upon finding the sticks, the other person would immediately know that a message was to be delivered, and he would go in search of the messenger and invite him into his home. Only after a polite conversation about other matters would the recipient finally ask if the messenger had some news to deliver.

Such “message plants” convey important information between members of the same village or tribe or between different tribes. As Reuben explained, each region of Aneityum had a certain plant species that represents that tribe when delivering a message to someone from another tribe. The plant that signifies Reuben’s area of Anelcauhat is a common coastal tree, Hibiscus tiliaceus, known as intophau in the language of Aneityum.

Several other villagers from the area near Anelcauhat told us that some plant species may convey more particular messages. Several small fern-like species of Selaginella, known as ngemas or necemas in Aneityumese (and as spikemosses in English), send a message that somebody has died. The messenger walks past someone with this plant in his hand or on his head or sometimes hands it to the other person directly, prompting that person to ask the messenger the name of the person who has passed away. Reuben and Yaiyaho Keith explained that a small yellow daisy, Wollastonia biflora, known as intop asiej or intop asyejora in their language, was placed on the doorstop of another person to indicate that he wished to break an agreement. Wopa Nasauman and Japanasei Lalep said that a special grass species, Isachne comate, known as nautahs in Aneityum, was used to send a message to a songwriter. When a musician received this plant, he recognized this as a request to compose a new song.

Sometimes the messages conveyed are connected to other uses of the plant. As Titiya Lalep explained, the small but beautiful fern Schizaea dichotoma, known as nirith u numu in Aneityum, is often rubbed on a fishing line to help attract fish, instead of using bait. By extension, when the fisherman returns from a successful day in his canoe, he places this same plant in his hat to signal that he caught some fish.

The beach-bean (Canavalia rosea), called nahajcgí in Aneityumese, is a low-growing vine with purple flowers that grows along the beach. Titya said this plant is used to communicate that a person would like to build a new house or establish a new garden at a particular spot. By wrapping this vine around a stick and placing it in the ground, he signals that the area is tabu, or forbidden, and that other people should stay away. Another vine, a parasitic plant known as inwouityuwun (with the scientific name Cassytha filiformis), may be carried by a stranger from another village to show that he is visiting in peace.

These examples of the many “message plants” found in Vanuatu demonstrate the rich interplay between plants, culture, and communication. Compared with email and mobile phones, the subtlety of traditional communication in Aneityum highlights a gentler and more refined means of conveying messages with greater respect and dignity. We could all learn a few lessons from these great gifts of the ancestors.

This post is based on an article by the authors that was published in Island Life magazine.

We are grateful to the Christensen Fund, The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, The National Geographic Society, and The National Science Foundation for their generous support of our ongoing work in Vanuatu as well as to the people of Vanuatu for their partnership in this work.