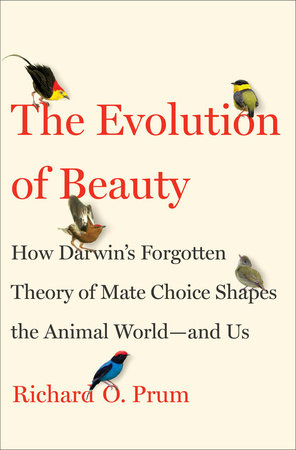

The Evolution of Beauty

Posted in From the Library on September 13 2018, by Esther Jackson

Esther Jackson is the Public Services Librarian at NYBG’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library where she manages Reference and Circulation services and oversees the Plant Information Office. She spends much of her time assisting researchers, providing instruction related to library resources, and collaborating with NYBG staff on various projects related to Garden initiatives and events.

In The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World—and Us, Richard O. Prum brings readers on a journey to understand the diversity of beauty in nature, and the evolutionary reasons for its existence. An ornithologist, Prum first focuses on avian ornamentation and attraction—a field with which he is intimately familiar; second on humans and our closer relatives—arguably a more theoretical undertaking. Prum follows Darwin’s theory of sexual selection which posits that “mate preferences can evolve for arbitrarily attractive traits that do not provide additional benefits to mate choice,” essentially (and very simplistically), a theory of beauty for the sake of beauty. While not necessarily at odds with Darwin’s theory of evolution, Victorian audiences rejected this theory based primarily on the disbelief that animals could discern beauty, and therefore disbelief that female individuals could use the metric of beauty to be agents of their species’ evolutionary progression.

In The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World—and Us, Richard O. Prum brings readers on a journey to understand the diversity of beauty in nature, and the evolutionary reasons for its existence. An ornithologist, Prum first focuses on avian ornamentation and attraction—a field with which he is intimately familiar; second on humans and our closer relatives—arguably a more theoretical undertaking. Prum follows Darwin’s theory of sexual selection which posits that “mate preferences can evolve for arbitrarily attractive traits that do not provide additional benefits to mate choice,” essentially (and very simplistically), a theory of beauty for the sake of beauty. While not necessarily at odds with Darwin’s theory of evolution, Victorian audiences rejected this theory based primarily on the disbelief that animals could discern beauty, and therefore disbelief that female individuals could use the metric of beauty to be agents of their species’ evolutionary progression.

In The Evolution of Beauty, Prum brings Darwin’s theory of sexual selection back to popular audiences, offering a convincing argument for its relevancy and importance in today’s evolutionary biology. In the book’s introduction, Prum writes: “I have decided to embrace beauty as a scientific concept because, like Darwin, I think it captures in ordinary language exactly what is involved in biological attraction. By recognizing sexual signals as beautiful to those organisms that prefer them—whether they are Wood Thrushes, bowerbirds, butterflies, or humans—we are forced to engage with the full implications of what it means to be a sentient animal making social and sexual choices. We are forced to entertain the Darwinian possibility that beauty is not merely utility shaped by adaptive advantage. Beauty and desire in nature can be as irrational, unpredictable, and dynamic as our own personal experiences of them.”

An ambitious book, different parts of The Evolution of Beauty may appeal to different readers. In particular, the ornithological sections are rich, immersive, and mesmerizing. Prum’s expertise, and his easy synthesis of his research and the research of others—notably Dr. Patricia Brennan, whose post-doctoral work at Yale was foundational for the “Make Way for Duck Sex” chapter—are a treat for anyone with an interest in the natural world. While those with a bit of existing knowledge of science might feel more comfortable with Prum’s style of writing, The Evolution of Beauty, a 2018 Pulitzer Prize finalist, is accessible to many different readers, and worth the time.