The Life & Works of Margaret Neilson Armstrong

Posted in People on March 29 2019, by Esther Jackson

Esther Jackson is the Public Services Librarian at NYBG’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library where she manages Reference and Circulation services and oversees the Plant Information Office. She spends much of her time assisting researchers, providing instruction related to library resources, and collaborating with NYBG staff on various projects related to Garden initiatives and events.

Margaret Neilson Armstrong (1867 – 1944) was a book designer, field collector, botanical illustrator, mystery writer, and more. She was born in 1867 in New York City to a wealthy and artistic family and raised along the Hudson River in Danskammer. Her father, Maitland Armstrong (1836 – 1918),[i] was a stained glass artist and diplomat. Her sister, Helen Maitland Armstrong (1869 – 1948),[ii] was a prominent stained glass artist, with whom she collaborated on a number of book design and illustration projects.

Armstrong’s first book cover design was published in 1890 when she was 23 years old. When she began to work in book design, Armstrong didn’t reveal that she was a woman, using only her initials – “M. N. Armstrong.” However, in 1892 she won an award for her book design work at the World’s Colombia Exposition in Chicago. From there she went on to design approximately 314 book covers, and by 1895 she established her stylized signature “M. A.” Prior to that, she had not always signed her designs.

The botanical artist Bobbi Angell wrote a wonderful article about her design work in the December 2018 issue of the Botanical Artist.[iii]

Armstrong’s book design work slowed in 1907, which some attribute to the introduction of paper book jackets, and other attribute to her wanting to work on her own projects instead of to continue designing for others.

After 1910, she decided that her next project would be to research and produce a field guide to the wild flowers of the Western United States and Canada. In her biography of Armstrong, Angell notes that during the period of 1887 to 1916, there were 13 field guides written and/or illustrated by women in the United States. Armstrong had vacationed in the American west, and couldn’t find a guide for the region. She convinced Putnam to publish a guide. Initially, she planned to work with botanist J. J. Thornber, but that arrangement fell through so she ended up writing and illustrating the entire work herself.

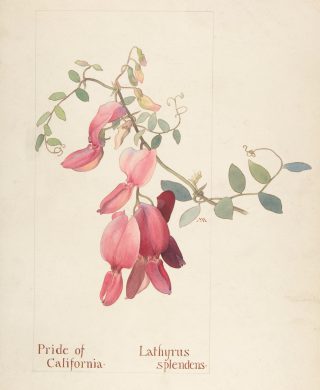

Over three years, between 1911 and 1914, she and two or three female companions travelled to parts of America and Canada west of the Rockies to collect and observe botanical vouchers. In 1911, at the age of 42, she ascended Victoria Glacier in Alberta, and is allegedly the first white woman to travel down into the basin of the Grand Canyon. She collected and pressed over 1000 specimens, some of them being species new to science. 188 of them are in the herbarium at NYBG. In 1986 her niece donated 52 of her original line drawings from this book to NYBG. Some of these drawings indicate the date and the location where they were produced. In total she produced 500 black and white drawings and 48 watercolors. The watercolors are held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Armstrong continued to produce both art and text for the remainder of her life, notably authoring the three mystery novels Murder in Stained Glass (1939), The Man With No Face (1940), and The Blue Santo Murder Mystery (1940). After a short illness, she died in 1944 in New York City, at the age of 76.

Further Reading

Espey, John Jenkins. A Checklist of Trade Bindings Designed by Margaret Armstrong. No. 16. Los Angeles: University of California Library, 1968.

Angell, Bobbi. Margaret Neilson Armstrong: Designer, Artist, Botanist, from the collections of NYBG and MET. v.24, no. 4., 2018

[i] http://research.frick.org/directoryweb/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=11795

[ii] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/416906

[iii] Reproduced with permission from the American Society of Botanical Artists. Article originally appeared in The Botanical Artist, (v.24, no.4, 2018) (c)ASBA