Inside The New York Botanical Garden

China

Posted in Around the Garden, Shop/Book Reviews on May 18 2011, by Selena Ahmed

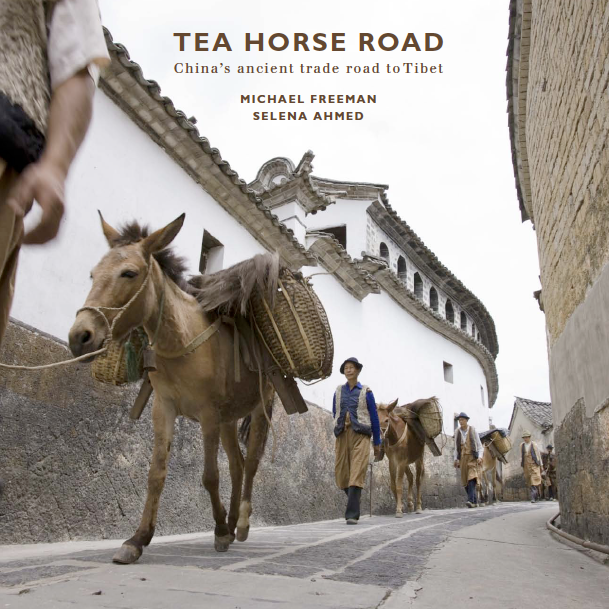

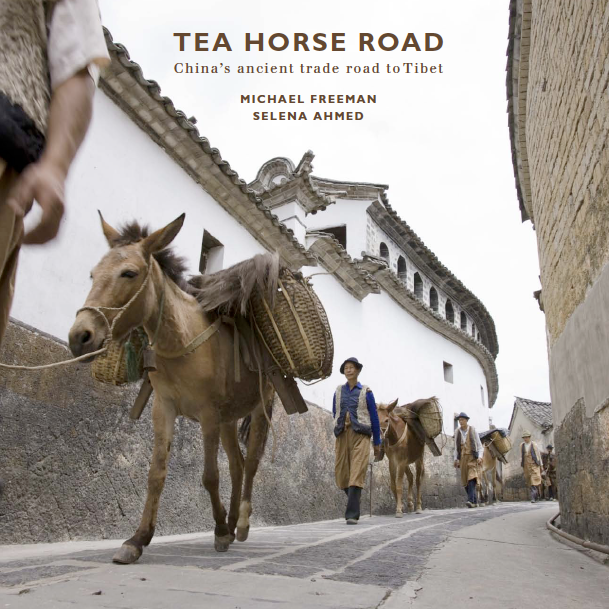

Ed. note: Selena Ahmed, ethnobotanist and author of the gorgeous new book Tea Horse Road will be at the Garden for a book signing this Saturday, May 21 at 3 p.m at Shop in the Garden. I first saw Selena’s book in a colleague’s office. The absolutely stunning photographs, taken by Michael Freedman, drew me in, but it is Selena’s tales that bring this fascinating book to life. We are currently working with Michael, who is traveling China, to put together a post of his photographs, so stay tuned. But why wait? Pick up a copy of Tea Horse Road this Saturday. You won’t be disappointed.

My new book, Tea Horse Road: China’s Ancient Trade Road to Tibet, with photographer Michael Freeman explores lives and landscapes along the world’s oldest tea trading route. Our journey starts in tropical montane forests in China’s southern Yunnan Province. This is the birthplace of the tea plant, Camellia sinensis (Theaceae). The cultural groups of Yunnan including the Bulang, Akha have produced and consumed tea for centuries for its well-being and stimulant properties. They traditionally grew tea plants as trees of several meters tall without the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides.

My new book, Tea Horse Road: China’s Ancient Trade Road to Tibet, with photographer Michael Freeman explores lives and landscapes along the world’s oldest tea trading route. Our journey starts in tropical montane forests in China’s southern Yunnan Province. This is the birthplace of the tea plant, Camellia sinensis (Theaceae). The cultural groups of Yunnan including the Bulang, Akha have produced and consumed tea for centuries for its well-being and stimulant properties. They traditionally grew tea plants as trees of several meters tall without the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides.

While tea cultivation spread where climatic conditions allowed, the practice of drinking tea reached far beyond. During the 7th century, the Tibetan kingdom to the north of Yunnan came into contact with tea, and the drink soon became central to the Tibetan people’s diet. Tea functioned to reduce the oxidative stress of Tibet’s high altitudes and as a dietary supplement in an environment with limited fruit and vegetable production. These same extreme conditions mean that tea has remained an imported item from tropical and sub-tropical areas in China’s Yunnan and Sichuan provinces. The demand for tea led to the creation of a network of trails extending more than 3,000 kilometers, carved through forests and mountains, with Lhasa at its core. This network collectively became known as the South West Silk Road or Cha Ma Dao, the Tea Horse Road.

However, tea was only one side of the trade equation: China was in constant search for warhorses that made its armies more mobile allowing the kingdom to maintain control over the empire. Abundant natural resources along with tea and horses were exchanged on the Tea Horse Road over the course of 2 millennia, linking cultures and natural resources beyond their surroundings. In its day, the Tea Horse Road touched the lives of many. These were the tea farmers on the southern mountains, the caravan leaders, the Tibetan lados skilled at traversing high passes and the porters with 100-kilo loads on their backs. This book is their story, narrated against the backdrop of some of the world’s most rugged and powerful landscapes.

Trade along the Tea Horse Road declined in the 20th century as horses ceased to have a major military use. Roads were paved allowing for more efficient transport, and policies and markets transitioned. As the Tea Horse Road acquires a historical presence, it is easy to forget its vital former role of maintaining community health, sustainable agriculture, livelihoods, and cultural exchange.

The research for my new book, Tea Horse Road: China’s Ancient Trade Road to Tibet, is partly based on my doctoral study at The New York Botanical Garden supervised by Dr. Charles M. Peters and guided by NYBG curators Drs. Amy Litt, Michael Balick, and Christine Padoch. My goal for this book was to disseminate findings from my doctoral study to a wide audience. The narrative is accompanied by Michael Freeman’s stunning visual documentation and is published by River Books.

Posted in Exhibitions, Science, The Edible Garden on September 2 2009, by Plant Talk

NYBG Student Travels to Asia to Trace Eggplant’s Roots

|

Rachel Meyer, a doctoral candidate at the Botanical Garden, specializes in the study of the eggplant’s domestication history and the diversity of culinary and health-beneficial qualities among heirloom eggplant varieties. She will hold informal conversations about her work at The Edible Garden‘s Café Scientifique on September 13. |

The eggplant (Solanum spp.) may not seem like the world’s most exciting food crop at first thought, but its history and diversity are actually quite intriguing. The common name, “eggplant,” actually covers more than one species, whose size, shape, color, and flavor are remarkably different throughout the world.

The eggplant (Solanum spp.) may not seem like the world’s most exciting food crop at first thought, but its history and diversity are actually quite intriguing. The common name, “eggplant,” actually covers more than one species, whose size, shape, color, and flavor are remarkably different throughout the world.

People have grown eggplants for over 2,000 years in Asia, and it is thought that eggplants were used as medicine before being selected over time to become a food. Many present-day cultivars of eggplants still contain medicinally potent chemical compounds, including antioxidant, aromatic, and antihypertensive, some of which might be the same compounds responsible for flavor as well.

If we can unravel the history of the eggplant’s domestication and investigate the health-beneficial and gastronomic qualities of heirloom eggplant varieties, we can promote specific varieties that may be useful to small-scale farmers, practitioners of alternative medicine, and eggplant lovers around the world.

I spent seven weeks in China and the Philippines last winter exploring how different ethnic groups use local eggplant varieties. These regions in Asia are important, because scientists are still not sure where eggplants were first domesticated (that is, selected by people over generations for desirable qualities instead of just harvested from the wild). We know it was in tropical Asia, but the written record doesn’t go back far enough to provide more clues. For that reason I also collected wild relatives of eggplant that might be the ancestor of the domesticated crop.

Read More

Posted in Programs and Events on August 7 2008, by Plant Talk

|

Written by Kate Murphy, a junior at Fordham University, with additional reporting by Genna Federico, a senior at St. John’s University; both are interns working in the Communications Department this summer. |

The 2008 Olympic Games open tomorrow in Beijing. And though China’s capital and second largest city seems a world away, you might be surprised to learn you can find a little bit of China right here at The New York Botanical Garden.

The Ruth Rea Howell Family Garden features a collection of Global Gardens—gardens planted and tended by volunteers in the spirit of different cultures and countries. Shirley Cheung, along with her husband, Frank, and her mother, Mrs. Miu, has maintained the Chinese Garden for over 15 years. As a schoolteacher, Shirley gets the summers off and likes to tend the Chinese Garden every day. She and her husband try to come in the early morning, usually before seven, to beat the heat.

The Chinese Garden contains plants both for show and for cooking, but Shirley prefers the latter, using almost everything she grows in her own kitchen. She likes to grow new things every year: This year they’re harvesting kohlrabi, a cultivar of cabbage, which she explains is popular in China and grows easily here. The leaves of kohlrabi, which cannot be found in food markets because they are discarded before being sold, are good for digestion. She suggests growing your own kohlrabi and steeping the leaves to make a tea for this purpose.

The Chinese Garden contains plants both for show and for cooking, but Shirley prefers the latter, using almost everything she grows in her own kitchen. She likes to grow new things every year: This year they’re harvesting kohlrabi, a cultivar of cabbage, which she explains is popular in China and grows easily here. The leaves of kohlrabi, which cannot be found in food markets because they are discarded before being sold, are good for digestion. She suggests growing your own kohlrabi and steeping the leaves to make a tea for this purpose.

Another plant you’ll have to grow at home if you want to enjoy Shirley’s recommendation is garlic. While most everyone can find garlic at a local supermarket, the green tops are harder to find. Shirley insists that this is the best part and tastes great on chicken or fish.

The Chinese Garden also contains three different kinds of beans, tomatoes weighing in at over two pounds, and bitter melon, a fruit that in China is said to “cure 100 diseases.” Another highlight is the pumpkin flower, which can be picked, dipped in egg batter, fried, and enjoyed as a delicious treat.

Shirley calls the Chinese Garden her “paradise,” and her doctor told her to continue, because it’s keeping her young.

“It’s a lot of work, but a lot of fun,” Shirley says. “It’s the best life you can have!”

My new book, Tea Horse Road: China’s Ancient Trade Road to Tibet, with photographer Michael Freeman explores lives and landscapes along the world’s oldest tea trading route. Our journey starts in tropical montane forests in China’s southern Yunnan Province. This is the birthplace of the tea plant, Camellia sinensis (Theaceae). The cultural groups of Yunnan including the Bulang, Akha have produced and consumed tea for centuries for its well-being and stimulant properties. They traditionally grew tea plants as trees of several meters tall without the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides.

My new book, Tea Horse Road: China’s Ancient Trade Road to Tibet, with photographer Michael Freeman explores lives and landscapes along the world’s oldest tea trading route. Our journey starts in tropical montane forests in China’s southern Yunnan Province. This is the birthplace of the tea plant, Camellia sinensis (Theaceae). The cultural groups of Yunnan including the Bulang, Akha have produced and consumed tea for centuries for its well-being and stimulant properties. They traditionally grew tea plants as trees of several meters tall without the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides.

The eggplant (Solanum spp.) may not seem like the world’s most exciting food crop at first thought, but its history and diversity are actually quite intriguing. The common name, “eggplant,” actually covers more than one species, whose size, shape, color, and flavor are remarkably different throughout the world.

The eggplant (Solanum spp.) may not seem like the world’s most exciting food crop at first thought, but its history and diversity are actually quite intriguing. The common name, “eggplant,” actually covers more than one species, whose size, shape, color, and flavor are remarkably different throughout the world.