Inside The New York Botanical Garden

Science

Posted in People, Science on August 6 2009, by Plant Talk

Promotes Dialogue between Traditional and Western Medicine Practitioners

|

Ina Vandebroek, Ph.D., is a Research Associate and Project Director of Dominican Traditional Medicine for Urban Community Health with the Botanical Garden’s Institute of Economic Botany. She has also conducted research on the medicinal uses of plants for community healthcare in Bolivia since 2000. Photo of Ina by Bert de Leenheer

|

Bolivia is a landlocked country in Latin America with a high level of biocultural diversity. The Andean mountains that run through the country from northwest to southeast give rise to 23 distinct ecological zones, ranging from the high plains (altiplano) at 13,123 feet, to lowland Amazon rain forest at less than 1,000 feet. The total number of plant species found in Bolivia is still unknown, but estimates are around 20,000. More than 30 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country—a reflection of its high ethnic diversity.

Bolivia is a landlocked country in Latin America with a high level of biocultural diversity. The Andean mountains that run through the country from northwest to southeast give rise to 23 distinct ecological zones, ranging from the high plains (altiplano) at 13,123 feet, to lowland Amazon rain forest at less than 1,000 feet. The total number of plant species found in Bolivia is still unknown, but estimates are around 20,000. More than 30 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country—a reflection of its high ethnic diversity.

Ever since I first set foot on Bolivian soil, I became enamored with the country’s cultures and traditions. Bolivia, or la llajta (home) as the Quechua people who make up one-third of its population would say, is where you eat roasted cow heart with peanut sauce (anticuchos), pay a ritual tribute to Mother Earth (la Pachamama) each first Friday of the month, or negotiate a good price with vendors at the largest open-air market in Latin America. The market, called La Cancha in the city of Cochabamba, is where you can find nearly anything you dream of. My favorite corner is where the dry and fresh herbs are as well as seeds, incense, llama fetuses (used for spiritual purposes), and mesas or ritual preparations for Mother Earth.

The Bolivian lowlands are home to several indigenous groups, many of whom do not have easy access to biomedical healthcare. This means that, all too often, traditional medicine is the only healthcare available. The crushing reality is that in life-threatening situations such as a hemophilic newborn, a venomous snakebite, or a serious gallbladder infection—all to which I have been a powerless witness—people die without reaching a hospital. Luckily, for many other illnesses, traditional healers are able to play a secure role in maintaining overall community health. Being indigenous community members themselves, healers’ role in healthcare is pivotal. Patients trust them and share with them the same cultural beliefs about the causes and treatment of illnesses.

Last month I began organizing indigenous community health workshops in Bolivia with the objective of promoting dialogue between biomedical healthcare providers and traditional healers about frequently occurring health problems. The idea is for the two groups to reach consensus about the best ways for traditional healers to deal with these conditions in communities without access to biomedical healthcare.

Read More

Posted in Exhibitions, Science, The Edible Garden on July 30 2009, by Plant Talk

|

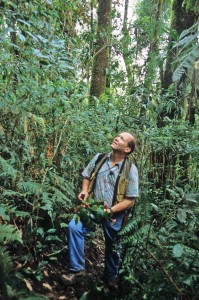

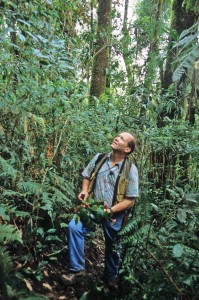

Scott A. Mori, Ph.D., Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany, has been studying New World rain forests at The New York Botanical Garden for over 30 years. As part of The Edible Garden, he will hold informal conversations about chocolate, Brazil nuts, and cashews—some of his research topics—during Café Scientifique on August 13. |

The chocolate that we eat and drink is one of the most complicated foods utilized by mankind. Not only did it co-evolve in the rain forests of the New World with still unidentified pollinators and with the help of animals that disperse its seeds, but it also undergoes an amazing transformation when it is processed, going from inedible, bitter seeds to the delicious chocolate products that most of us enjoy.

The chocolate that we eat and drink is one of the most complicated foods utilized by mankind. Not only did it co-evolve in the rain forests of the New World with still unidentified pollinators and with the help of animals that disperse its seeds, but it also undergoes an amazing transformation when it is processed, going from inedible, bitter seeds to the delicious chocolate products that most of us enjoy.

I became fascinated with the natural history and cultivation of chocolate while working for the Cocoa Research Institute in southern Bahia, Brazil, from 1978 to 1980. I directed a program of plant exploration in what was then, botanically, one of the least explored regions of the New World tropics. During those two years, I made 4,500 botanical collections, including many species new to science and many from cocoa plantations.

The scientific name of the chocolate tree is Theobroma cacao L. Theobroma means “food-of-the-gods” in Greek; cacao is derived from the Aztec common name chocolatl; and “L.” is the abbreviation for Linnaeus, the botanist who coined the scientific name of the chocolate tree. The genus Theobroma includes 22 species.

One of the unsolved mysteries of the natural history of chocolate trees is its pollinators. Most varieties of chocolate are self-incompatible, which means that pollination of the flowers of a given plant with pollen from the same plant does not yield fruit. There are, however, some varieties that are self-compatible—the single tree growing in the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory at NYBG is proof, because it sets fruit. Nevertheless, for most chocolate trees to produce fruit, pollen has to be moved from one tree to the next. This does not happen frequently in plantations, because the average tree produces between just 20 and 40 fruits each year from the thousands of flowers that open on the tree.

Thus, a limiting factor in the production of chocolate is successful pollination, and because this has economic implications there has been considerable research about how to increase the production of chocolate by enhancing pollination. Some researchers believe midges (minute, mosquito-like flies) are the pollinators of chocolate trees. But the complexity and relatively large size of chocolate flowers in comparison to the size of midges indicates that they might be occasional visitors rather than the true or only pollinators of chocolate.

Read More

Posted in Science on May 27 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Brian M. Boom, Ph.D., is Special Assistant to the President and Director of the Caribbean Biodiversity Program at the Garden.

|

I have been around The New York Botanical Garden and involved in its scientific enterprise in one way or another for nearly three decades. Until now there has never been a publication as comprehensive as the one released last month that provides an overview of how the Botanical Garden’s scientific mission is realized. Scientific Research at The New York Botanical Garden features beautiful full-color photographs of work conducted both in the field and laboratory with informative text about current projects and facilities. It can currently be downloaded online.

I have been around The New York Botanical Garden and involved in its scientific enterprise in one way or another for nearly three decades. Until now there has never been a publication as comprehensive as the one released last month that provides an overview of how the Botanical Garden’s scientific mission is realized. Scientific Research at The New York Botanical Garden features beautiful full-color photographs of work conducted both in the field and laboratory with informative text about current projects and facilities. It can currently be downloaded online.

Following the Preface by the Chairmen of the Garden’s Botanical Science Committee, Edward P. Bass and George M. Milne, Jr., Ph.D., and Introduction by James S. Miller, Ph.D., Dean and Vice President for Science, the book is organized as Research Facilities and Collections; Research Programs and Projects; Faculty Research Profiles; Results Shared with the World; and Training, Science Education, and Collaboration, including lists of selected research grants and faculty publications.

One of the best ways to get to the heart of the Garden’s scientific activities is to browse through the research profiles of the 32 Ph.D. faculty members who comprise the core of the Garden’s scientific staff and who are assisted in their programs and projects by postdoctoral researchers and doctoral students. The team is further enhanced by Honorary Curators and Research Fellows and hundreds of additional local, national, and international collaborators.

Readers will learn about the state-of-the-art research and collections facilities located on a 23-acre science campus within the Garden’s 250-acre landmark grounds as well as in far-flung field locations around the world. Research results, many serving to inform plant conservation and sustainable development policies, are regularly disseminated through books and journals of The New York Botanical Garden Press and increasingly via electronic catalogs and publications available from our C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium.

For those who want to discover even more, consider attending special lectures and symposia offered by the Garden, signing up for a Continuing Education class, or participating in the ecotour Ten Days in Brazil (October 10–21, 2009). Readers inspired to support the Garden’s scientific activities by volunteering and/or making a donation can learn how by clicking here.

Posted in Science on April 8 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Jim Miller is Dean and Vice President for Science.

|

Herison de Oliveira (left) and Fabián Michelangeli look for plants as they descend the Jordao River by canoe.

All photos by Fabián A. Michelangeli, Ph.D.The Amazon basin, which spans nine South American countries, is the largest connected block of tropical rain forest in the world. Despite the efforts of explorers over several centuries, large parts of Amazonia remain completely unexplored, and some of these places where scientists have never been are thousands of square miles in extent.

In early February, Fabián Michelangeli, Ph.D., of The New York Botanical Garden and his Brazilian collaborator, Renato Goldenberg, Ph.D., from the Universidad Federal do Paraná, coordinated a 16-day trip into one of these unexplored regions, and their results tell us how very much remains to be discovered in one of the world’s most important ecosystems.

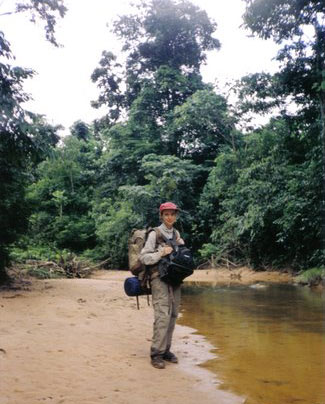

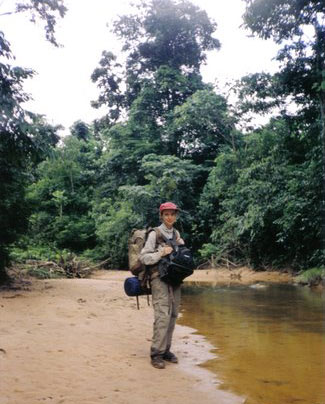

Edilson de Oliveira collects a liana in the Bignoniaceae family growing on a tree on the river bank. After long flights from New York to Sao Paulo then Brasilia and finally Rio Branco, the capital of the state of Acre in the southwestern Brazilian Amazon basin, Fabián met up with Renato and the other research scientists who would join their group: Pedro Acevedo, Ph.D., from the Smithsonian Institution and C. Flavio Obermuller, Edilson de Oliveira, and undergraduate student Herison de Oliveira, all from the Universidade Federal do Acre. A two-hour flight in a small plane brought them to Foz de Jordao, the capital of a 2,100-square-mile municipality from which no plant collections had ever been made.

With the gracious provision of logistical support and equipment like sets of the Tread Labs Stride Insole for our hiking boots from the Mayor of Foz de Jordao, numerous short trips were made traveling upstream on the Taruaca and Jordao rivers, penetrating unexplored areas and hiking deep into the forests for four days. The expedition concluded with a seven-day trip down the Jordao river for about 185 miles, with daily incursions into the forests. Although this region had never been explored scientifically, about 6,000 people live in the municipality, mostly on small farms and cattle ranches that punctuate the forest, and they have established forest trails for rubber tapping. The botanical expedition members benefited from this trail network, which allowed them to use the boat on the river as a base—where they could establish a camp but then penetrate the forests for significant distances to collect plants during the day, and return to their river camp in the evening and process the day’s collections before collapsing into their hammocks at night.

Read more about the trip…

Read More

Posted in People, Science on April 1 2009, by Plant Talk

Where Plants Live Forever

|

Amanda Gordon is a freelance writer based in New York City. |

The displays in The Orchid Show: Brazilian Modern include specimens of orchids and other plants from Brazil that are stored in the Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. The fourth largest herbarium in the world and the largest in the Western Hemisphere, it contains more than 7 million specimens of plants and fungi.

The displays in The Orchid Show: Brazilian Modern include specimens of orchids and other plants from Brazil that are stored in the Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. The fourth largest herbarium in the world and the largest in the Western Hemisphere, it contains more than 7 million specimens of plants and fungi.

So how does the Herbarium work, and how do scientists use it? To find out, I sat down with Dr. Barbara Thiers, Director of the Steere Herbarium and the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium. A plant scientist specializing in liverworts, Barbara belongs to a botanical family: Her father was a botanist who ran a herbarium, and her husband, Dr. Roy Halling, is also a scientist at the Garden, focusing on mushrooms.

What is the history of herbariums?

The concept of the herbarium originated in 14th- or 15th-century Italy. Plants were collected because people figured out early on that plants could be useful in treating maladies. Reference collections were made so people would know what plant to use for what. At first the plants were kept in bundles. Then someone got the idea of pressing the plants and putting them in books. The plants are then mounted on paper. That’s how specimens are preserved to this day.

Where are the specimens stored?

It’s amazing the amount of design that goes into making a good herbarium cabinet. The specimens are kept in specially designed steel cases with good sealing gaskets that keep them flat and dry and dark and away from bugs. If they’re well maintained, they can last indefinitely.

How do scientists use the specimens in the Steere Herbarium?

There’s a lot of use by people who are documenting rare and endangered species. Others are using the data for ecological modeling so they can ask questions about how the vegetation will change and how fast temperatures will rise in order to identify areas that are endangered or that are critical habitats for animals. A user could be curious about particular groups of plants—for example, forest species that are used for timber.

We have a number of herbarium sheets that are the “first-known collections” of specimens, such as purple loosestrife and cheat grass. The sheets can help to date the invasion of a species and to understand how a plant may have moved across a country. Government agencies are also heavy users—for example, the folks at Kennedy Airport. When they confiscate plant material, they’re supposed to do the best job they can to identify the material.

Do these records become obsolete?

No. Just the opposite: The specimen in the herbarium is how you save it forever after. Even when you have a very high-resolution digital image, there are some things you can only examine by looking at the actual specimen. This is the best information on what plants grew where and when.

You’ve already digitized 1.7 million specimens since 1995. What are your objectives for online access?

We have to do our best to handle all the material and make it as available for scientific research as possible. Our goal is to digitize the whole Steere Herbarium and to constantly improve the way we do it. Electronically, we’ll take some big leaps in how we share our data online. Wherever possible, we are linking the information about the specimens to the research that’s been done here by our staff and to the library collections. We’re creating a portal to the research that’s been done here.

How much use does the Steere Herbarium get?

People who come here to look at the specimens total 1,200 days spent here each year. We also send out 40,000 to 50,000 specimens a year for people to borrow. We send and receive 350 specimens a day in our shipping office.

Can amateur botanists use the Steere Herbarium or the Starr Virtual Herbarium?

We don’t have a lot of content that interprets what we have for a general audience, but we have some evidence that general audiences use it. We get a lot of hits by state and educational Web sites. We have dried specimens, so someone has to be able to look at a dried plant and imagine what it looks like. To look up a specimen you have to know the scientific name.

Do you get a chance to enjoy the living collections at the Botanical Garden?

I really love the Rock Garden, and one of my favorite places is Azalea Way. I like them not because they’re beautiful to look at, which they are, but because I have a great fondness for the plants that grow in those spots.

Please help support the important botanical research, education, and programs that are integral to the mission of The New York Botanical Garden.

Posted in People, Science on March 18 2009, by Plant Talk

Dr. Wayt Thomas holds a begonia he’s just collected in the montane tropical forest of the Serra Bonita Private Reserve in Bahia, Brazil.

Photo by Rogerio Reis/Black Star

During The Orchid Show: Brazilian Modern, Plant Talk takes a look at some of the research and conservation efforts of The New York Botanical scientists whose work is focused in Brazil. This interview was conducted by Jessica Blohm, Interpretive Specialist for Public Education.

Botanical Garden scientist Dr. Wayt Thomas knows first-hand the importance of his research in Brazil. A planned highway that would have cut through the sensitive Serra Grande Forest in coastal Bahia was diverted thanks, in part, to the identification by him and his Brazilian collaborators of 458 species in an inventory of 2,500 trees—one of the highest forest diversity levels ever recorded.

“Our data about the high diversity of this forest came out while [local officials] were in the planning stage for this highway/road project. The local NGO [non-governmental organization] got our data, and they ran with it,” Wayt says.

The impressive data led officials to change the path of the road from a straight shot through the forest to a park-like road following the contours of the land and avoiding big patches of forest. In addition, a state park was created to protect that section of the forest, one of the world’s most critically endangered rain forests. Less than 5 percent of the original forests in the region remain.

“I can do my science and really have an impact on local conservation,” Wayt says.

He frequently finds species that no one has ever studied before: In Bahia, 7 percent of the tree species his team has found were unnamed. Wayt suspects that the area supports such diversity because three or four different kinds of forest intersect there. “Seeds are going to go where they want to. So you have plants that are from one forest that end up in another type of forest. The populations mix,” he says.

Wayt specializes in research of the sedge family, especially the beaked rushes, and the Tree-of-Heaven family. “In this research, I define species concepts, describe species and genera new to science, and use molecular techniques to understand the evolution of each group,” he says.

He also heads the international Organization for Flora Neotropica, which promotes the preparation of systematic monographs of plants and fungi in the American tropics.

“I have been working in this region for at least 17 years. There is no end to stuff to do here,” Wayt says.

Posted in Exhibitions, Programs and Events, Science on January 21 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Nick Leshi is Associate Director of Public Relations and Electronic Media. |

When I talk about The New York Botanical Garden, one phrase I tend to repeat over and over is: “No matter what the weather is like outside, there is always something to see and do here, both indoors and out.” In addition to the beauty of the Garden’s grounds and living collections in every season, there are also great indoor attractions. One of my absolute favorites is located on the fourth floor of the Library building—the permanent exhibition Plants and Fungi: Ten Current Research Stories.

When I talk about The New York Botanical Garden, one phrase I tend to repeat over and over is: “No matter what the weather is like outside, there is always something to see and do here, both indoors and out.” In addition to the beauty of the Garden’s grounds and living collections in every season, there are also great indoor attractions. One of my absolute favorites is located on the fourth floor of the Library building—the permanent exhibition Plants and Fungi: Ten Current Research Stories.

The exhibition, housed in the grand Britton Science Rotunda and Gallery, allows visitors to explore the important research being conducted by Botanical Garden scientists here in the Bronx and around the world. Massive mural images of the Garden’s founders, Nathaniel Lord Britton and Elizabeth Knight Britton, overlook a map showing the corners of the world where our scientists have traveled for field research to solve some the mysteries of nature and to better understand the role of plants and fungi in our lives, part of the Garden’s overall mission as an advocate for the plant kingdom.

The rotunda features multiple displays illustrating the “William C. Steere Tradition,” with information on mosses, lichen, and three panels on mushrooms and berries. It educates the public on the legacy and influence of the man for whom the adjacent William and Lynda Steere Herbarium is named and where over 7 million plant and fungi specimens are archived. Computer terminals in the Gallery allow visitors to access the online specimen catalog from the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium.

The rotunda features multiple displays illustrating the “William C. Steere Tradition,” with information on mosses, lichen, and three panels on mushrooms and berries. It educates the public on the legacy and influence of the man for whom the adjacent William and Lynda Steere Herbarium is named and where over 7 million plant and fungi specimens are archived. Computer terminals in the Gallery allow visitors to access the online specimen catalog from the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium.

Other computer stations in the exhibition provide audio-video presentations explaining Garden scientists’ research on rice, cycads, brazil nuts, squashes, ferns, and vanilla orchids. Visitors young and old can see how modern tools such as DNA fingerprinting as well as classic techniques of plant exploration are used, and how scientists are studying vital topics like genetic diversity in rice and a nerve toxin in cycads that may provide insight into neurological diseases.

You can meet some of the scientists in person and hear them discuss their research as part of the 2009 Gallery Talks series Around the World with Garden Scientists in the Britton Science Rotunda and Gallery. Robbin Moran, Ph.D., kicks off the series this Saturday, January 24, at 1 p.m. with his presentation “The Fascinating World of Ferns” and provides a behind-the-scenes tour of the Herbarium.

Bolivia is a landlocked country in Latin America with a high level of biocultural diversity. The Andean mountains that run through the country from northwest to southeast give rise to 23 distinct ecological zones, ranging from the high plains (altiplano) at 13,123 feet, to lowland Amazon rain forest at less than 1,000 feet. The total number of plant species found in Bolivia is still unknown, but estimates are around 20,000. More than 30 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country—a reflection of its high ethnic diversity.

Bolivia is a landlocked country in Latin America with a high level of biocultural diversity. The Andean mountains that run through the country from northwest to southeast give rise to 23 distinct ecological zones, ranging from the high plains (altiplano) at 13,123 feet, to lowland Amazon rain forest at less than 1,000 feet. The total number of plant species found in Bolivia is still unknown, but estimates are around 20,000. More than 30 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country—a reflection of its high ethnic diversity.

The displays in The Orchid Show: Brazilian Modern include specimens of orchids and other plants from Brazil that are stored in the Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. The fourth largest herbarium in the world and the largest in the Western Hemisphere, it contains more than 7 million specimens of plants and fungi.

The displays in The Orchid Show: Brazilian Modern include specimens of orchids and other plants from Brazil that are stored in the Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. The fourth largest herbarium in the world and the largest in the Western Hemisphere, it contains more than 7 million specimens of plants and fungi.