Once Frozen in Ice, Now Frozen in Time: Artifacts of an Arctic Voyage

Posted in Nuggets from the Archives on September 23, 2016 by Lansing Moore

Sarah Dutton is a project coordinator in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, where she is working on a project to digitize the Steere Herbarium’s collection of algae.

It is 1879, and for months you have been living aboard a creaking wooden steamship trapped in miles of shifting Arctic sea ice. When you venture above deck, the air is icy as you gaze across the polar landscape. Among your companions are several officers, 21 crewmen, six other European scientists of various disciplines, and a few hundred indigenous Chukchi people who live nearby.

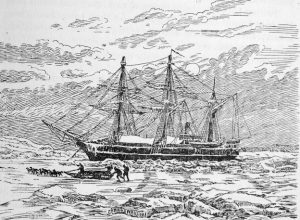

Such was the experience of Dr. Frans Reinhold Kjellman, a botanist aboard the SS Vega during the Swedish Vega Expedition. The New York Botanical Garden’s project to digitize the algae collection in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium has uncovered two algal specimens that Dr. Kjellman collected during this expedition, providing glimpses into a little-known but fascinating story of 19th century science and exploration.

The tale begins with Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, a Finnish-Swedish scientist and explorer, who had led many successful Arctic expeditions by the time he proposed the Vega Expedition. This time, he planned to circumnavigate the Eurasian continent via the Arctic Ocean and the Bering Strait, or “North East Passage,” to prove that this was a viable route between Europe and the Pacific. The scientists on board the Vega were prepared to gather data about the geography, hydrography, meteorology, and natural history of the Arctic, much of which was still unexplored by Europeans at the time. Kjellman, who had accompanied Nordenskiöld on three previous voyages, was an authority on Arctic algae.

The SS Vega departed Sweden on June 22, 1878. On September 3, the ship began to encounter sea ice. The explorers continued, hugging the coast and searching for a clear way through the increasing ice. However, by the end of September, the ice thickening in front them could no longer be broken by the ship’s hull. They had reached Kolyutschin Bay, the last bay before the Bering Strait, but a belt of ice less than 7 miles wide barred their passage. In his book, The Voyage of the Vega round Asia and Europe, Nordenskiöld expresses regret over time that could have been saved along the journey. He believed that had the ship arrived at Kolyutschin Bay just a few hours earlier, they would have been able to continue. To rub salt in the wound, Nordenskiöld later learned that an American whaler had been anchored only a couple of miles away in open water on the same day the Vega was frozen in.