Inside The New York Botanical Garden

The New York Botanical Garden

Posted in Photography, Wildlife on February 2 2011, by Plant Talk

It’s been a hard winter, and even though Punxsutawney Phil didn’t see his shadow today, we’re with our feathered friends. After this latest winter storm, we’re not quite sure spring is on the way, either. (Even though, let’s be honest, we know it’ll be here before we know it!)

One Obviously Exasperated Robin (photo by Ivo M. Vermeulen)

Even the Turkeys Had to be Careful About Where They Walked

(photo by Ivo M. Vermeulen)

Posted in Around the Garden on February 2 2011, by Plant Talk

The 50-acre, old growth Native Forest is the heart of the Garden. It is one of the reasons Nathaniel Lord Britton settled on this 250-acre plot in the Bronx as the place to build his dream Botanical Garden, it is home to at least one tree that was alive at the time of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, it is home to some of the Garden’s most fascinating residents, it is a place where scientists can study everything from global warming to genetics, and it is a very fine place to go for a stroll. The Forest is a vital part of not just the New York Botanical Garden, but also of New York City, and the world.

The 50-acre, old growth Native Forest is the heart of the Garden. It is one of the reasons Nathaniel Lord Britton settled on this 250-acre plot in the Bronx as the place to build his dream Botanical Garden, it is home to at least one tree that was alive at the time of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, it is home to some of the Garden’s most fascinating residents, it is a place where scientists can study everything from global warming to genetics, and it is a very fine place to go for a stroll. The Forest is a vital part of not just the New York Botanical Garden, but also of New York City, and the world.

For these reasons, and for so many more, we are delighted that the United Nations has declared 2011 “The International Year of Forests.” The UN says that the year is a “celebration of the vital role that forests play in people’s lives … amid growing recognition of the role that forests managed in a sustainable manner play in everything from mitigating climate change to providing wood, medicines and livelihoods for people around the world.”

We’ll be joining in on recognizing the International Year of Forests with a series of events throughout 2011 (but we’re not ready to announce them just yet). In the meantime, here are some other forest facts from the United Nations:

See the facts below.

Posted in Photography on February 1 2011, by Plant Talk

It’s been a few weeks since we announced a Photo Contest as part of Caribbean Garden, a reinterpretation of the permanent collection inside the historic Enid A. Haupt Conservatory. We’ve hit a few bumps along the way logistically, but that hasn’t effected the quality of the photos that you have entered! There are several weeks left in the contest, and another winter storm has barreled into the city to welcome February, so come enjoy the warmth of the Conservatory and snap a few pictures while you’re here!

To get you excited about participating, here are a few of the winners from the previous weeks’ contests.

Head below the jump to see the winners from the past two weeks of the contest!

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on February 1 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 26, 2011, Punta Arenas, Chile

January 26, 2011, Punta Arenas, Chile

We awoke on the morning of January 25 in Seno Agostini, having arrived there at about 4 a.m. Initially the journey was rough because of strong winds and large swells. Standing on the deck, but huddled close to the cabin, I was in awe of the weather. Since childhood in Florida, the U.S. capital of lightning, I have loved violent weather. On this day, the wind howled and the boat was tossed and turned by the rough seas; every few seconds waves would crash over the deck. To be on a small ship amidst such weather is amazing. Of course it helps to have a ship that you have faith in and a reliable crew. A few of our group felt a bit queasy, but no real problems came up (pun intended). After about an hour and a half we entered a narrower channel and the seas were calmer. Only then was dinner served.

Coming out on deck the next morning the scenery was spectacular. We had come to this spot because in 1929 a Finnish bryologist, Heiki Roivainen, visited the site and, in an alpine stream, collected a moss that has not been found since. Because this is a moss that is part of Juan’s doctoral work, he was anxious to find it again. The site is called Mt. Buckland, and it rises to over 6,000 feet but is mostly snow-covered above. Supposedly the moss was collected at about 2,000 feet in an alpine stream. All around us rugged peaks rose to the sky, all with either snow or glaciers. At least for a short time the sun shone brightly.

So, optimistically, Jim and Juan headed up the slopes of Mt. Buckland. Blanka and I chose to visit a southern beech forest on the other side of the sound that had a large glacier at its back side. It was about a 20 minute zodiac ride across the sound but as soon as we hit the rocky beach we knew we were in a special place. Numerous small, glacier-fed streams wound their way through the landscape and occasional large rock outcrops promised multiple microhabitats for bryophytes. Once Blanka entered the forest, about 10 yards past the coastal scrub, it took me about an hour to get her to move ahead. The forest floor was carpeted with a thick layer of liverworts that swallowed our boots with every step. Trees were sheathed with bryophytes and lichens, often several times the diameter of the trunks themselves. We worked our way through the forest toward the glacier, marveling at the diversity and sheer biomass of bryophytes in the forest.

So, optimistically, Jim and Juan headed up the slopes of Mt. Buckland. Blanka and I chose to visit a southern beech forest on the other side of the sound that had a large glacier at its back side. It was about a 20 minute zodiac ride across the sound but as soon as we hit the rocky beach we knew we were in a special place. Numerous small, glacier-fed streams wound their way through the landscape and occasional large rock outcrops promised multiple microhabitats for bryophytes. Once Blanka entered the forest, about 10 yards past the coastal scrub, it took me about an hour to get her to move ahead. The forest floor was carpeted with a thick layer of liverworts that swallowed our boots with every step. Trees were sheathed with bryophytes and lichens, often several times the diameter of the trunks themselves. We worked our way through the forest toward the glacier, marveling at the diversity and sheer biomass of bryophytes in the forest.

Barberries, bryophytes, and icebergs, oh my! More below.

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on January 31 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 24, 2011, Seno Chasco, just north of isthmus to Brecknock Peninsula, Chile, 54° 34’S, 71° 39’W

January 24, 2011, Seno Chasco, just north of isthmus to Brecknock Peninsula, Chile, 54° 34’S, 71° 39’W

Last night, after I had finished my work for the day, I was enjoying the night out on the deck (i.e., a lull in the rain) and watching Blanka, Jim and Juan down in the hold putting their collections on the dryer. They have each been consistently excited about going out into the field everyday, no matter what the weather. Back on the ship they happily go through their collections. Watching their interest and energy makes me feel good that I am able to provide them with this opportunity. It also gives me something to look forward to, for those future expeditions when, in upcoming years, new teams of bryologists will accompany me to this spectacular region. Although it is something that never occurred to me before, this truly is one of the highlights of this project, being able to see the excitement on the faces of bryologists who have never seen such a mossy paradise before, and knowing that I could give them this gift (thanks to the National Science Foundation).

More on Cape Horn's mossy paradise below.

Posted in Photography on January 31 2011, by Plant Talk

Looking down the main pathway of the Perennial Garden.

(photo by Ivo M. Vermeulen)

Posted in Photography on January 30 2011, by Plant Talk

From the roof of the Library Building.

(photo by Ivo M. Vermeulen)

Posted in Photography on January 29 2011, by Plant Talk

The snow gathering on this Magnolia kobus near the Visitor Center makes it look like something out of a fantastic dream.

(photo by Ivo M. Vermeulen)

Posted in Science on January 28 2011, by Plant Talk

| Amy Litt is Director of Plant Genomics and Cullman Curator. |

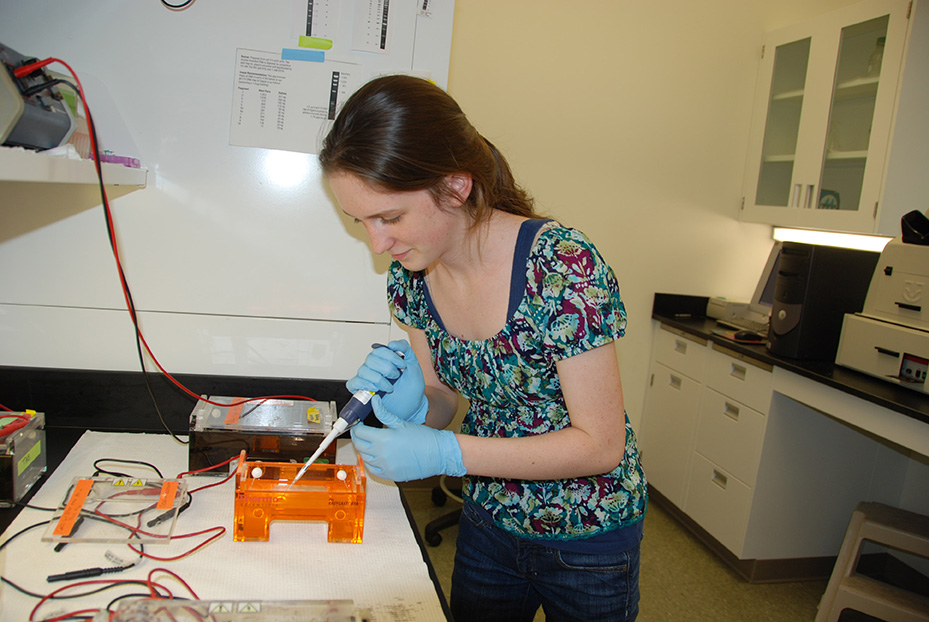

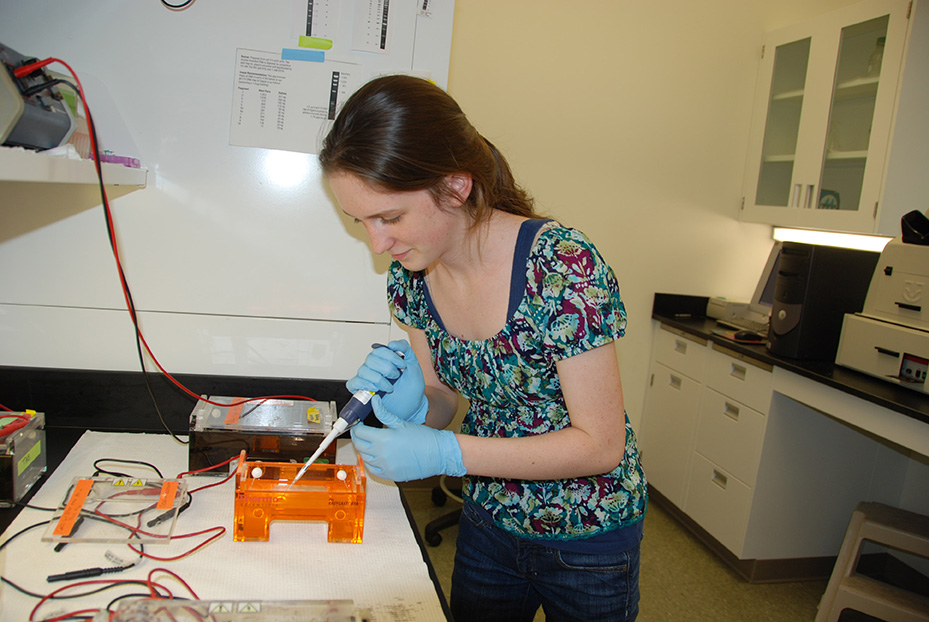

Grace Phillips, a senior at Mamaroneck High School, has been named a finalist in the prestigious Intel Science Talent Search. Phillips worked as a Cullman intern at the Garden for more than two years with graduate student Rachel Meyer on research related to the domestication of the eggplant. It is for this research that she is being recognized. In March, Grace will travel to Washington, D.C.,–along with the 39 other finalists–to participate in final judging, display her work to the public, meet Nobel laureates, and to find out if she has won the top prize of $100,000.

Grace Phillips, a senior at Mamaroneck High School, has been named a finalist in the prestigious Intel Science Talent Search. Phillips worked as a Cullman intern at the Garden for more than two years with graduate student Rachel Meyer on research related to the domestication of the eggplant. It is for this research that she is being recognized. In March, Grace will travel to Washington, D.C.,–along with the 39 other finalists–to participate in final judging, display her work to the public, meet Nobel laureates, and to find out if she has won the top prize of $100,000.

In addition to being a tasty treat, the eggplant has been also cultivated for ages–from India, to China, and to the Pacific Islands–for the plant’s medicinal values. Hundreds, if not thousands, of local variations of the eggplant exist throughout Asia, varying widely in size, shape, color, and flavor; and are used medically for a variety of purposes. It is likely that the medicinal values of the eggplant come from a variety of potent antioxidant compounds found within the fruits.

Phillips studied what impact the role of centuries of human selection–based on taste and medicinal properties–have had upon the eggplant genome. This involved first studying the chemicals that are thought to be responsible for the gastronomic and therapeutic properties of the various local variations (also known as landraces). By correlating the presence of specific antioxidant compounds to specific tastes and medicinal attributes Phillips attempted to answer a simple question: Are certain medicinal uses of eggplants always associated with high concentrations of specific compounds?

After determining the various chemical compounds within the eggplants, Grace then began to study the genes that are directly related to the synthesis of these compounds, looking for correlations between gene activity and compound abundance. Phillips was then able to put all this information together and pose one final question: Are certain taste and medicinal qualities correlated with high levels of specific gene? Or, in other words: As humans selected for eggplants with specific culinary and therapeutic properties, what effect did this intervention have on the eggplant genome and on the plant’s gene functions?

Grace is one of seven finalists from New York State, second only to California’s 11 finalists. She appears to be the only finalist working in the field of plant sciences, and one of only a handful of students studying organismal diversity/evolutionary questions. Grace’s work continues a long heritage of scientific study at The New York Botanical Garden on questions of plant diversity, human-plant interactions, and plant conservation. Everyone here at the Garden applauds Grace’s fantastic work and wishes her the best of luck in March!

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on January 28 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 23, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Puerto Consuelo, Seno Chasco, Chile, 54° 32’S, 71° 31’W

January 23, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Puerto Consuelo, Seno Chasco, Chile, 54° 32’S, 71° 31’W

Although I am writing this blog daily, it is often impossible to send it. We were told that the modem that we rented would work anywhere, but in reality it needs a clear view to the north. Often times, though, our ship is anchored in a sheltered area with tall, snow-capped mountains on most sides of us. With the severe and changeable weather here, the saying “any port in a storm” takes on extra meaning! So, I continue to write and send them out whenever the modem decides it is in the mood.

Early this morning (5 a.m.) the captain moved the ship from our previous site to the sound directly west. When I awoke to the engine starting, I knew it would be 3-4 hours before we reached our next site, and that we could sleep in for awhile. Maybe an hour later it became obvious that we had left the protected sound for more open waters. The ship started rocking violently. For most of us, it was like rocking a baby in a cradle and put us back to sleep. Only one person felt a little queasy and had to take something for seasickness. Fortunately, so far, no one has actually gotten sick. In my previous trip to the region, on our second day our, we hit a large storm which crashed 12 foot waves over the ship for hours on end. As our bunkroom was transformed into a vomitorium, I was the only non-crew member who didn’t get sick. Since our bunkroom on this trip has minimal ventilation at best, it is a true blessing that this time no one has gotten sick.

It was immediately obvious when we entered the next sound, suddenly the waters were much calmer. At about 8:30 a.m., the ship stopped. I assumed that meant we were at our next site. Such was not the case. Rather, we were taking on fresh water. To do this, the ship will pull up to a waterfall and one of the crew scrambles up the cliff face with a plastic bucket that is outfitted with a hose coming out of the bottom of it. The bucket goes into the waterfall and the end of the hose is placed into the hatch of the water tank, on top of the ship. We are in a totally uninhabited place, one that gets around 12 feet of rain a year, much of which at higher elevations falls as snow. So even in mid-summer, given that there are no large mammals to pollute it, the snow-melt water is pure and cold, which is good because it is the only fresh water we have. After watching the crew member (José) go up the cliff face like a monkey, I told him now we just need to teach him to collect mosses!

Read more about Bill's adventures below.

The 50-acre, old growth

The 50-acre, old growth